Understanding cause-neutrality

March 10, 2017

Executive summary1

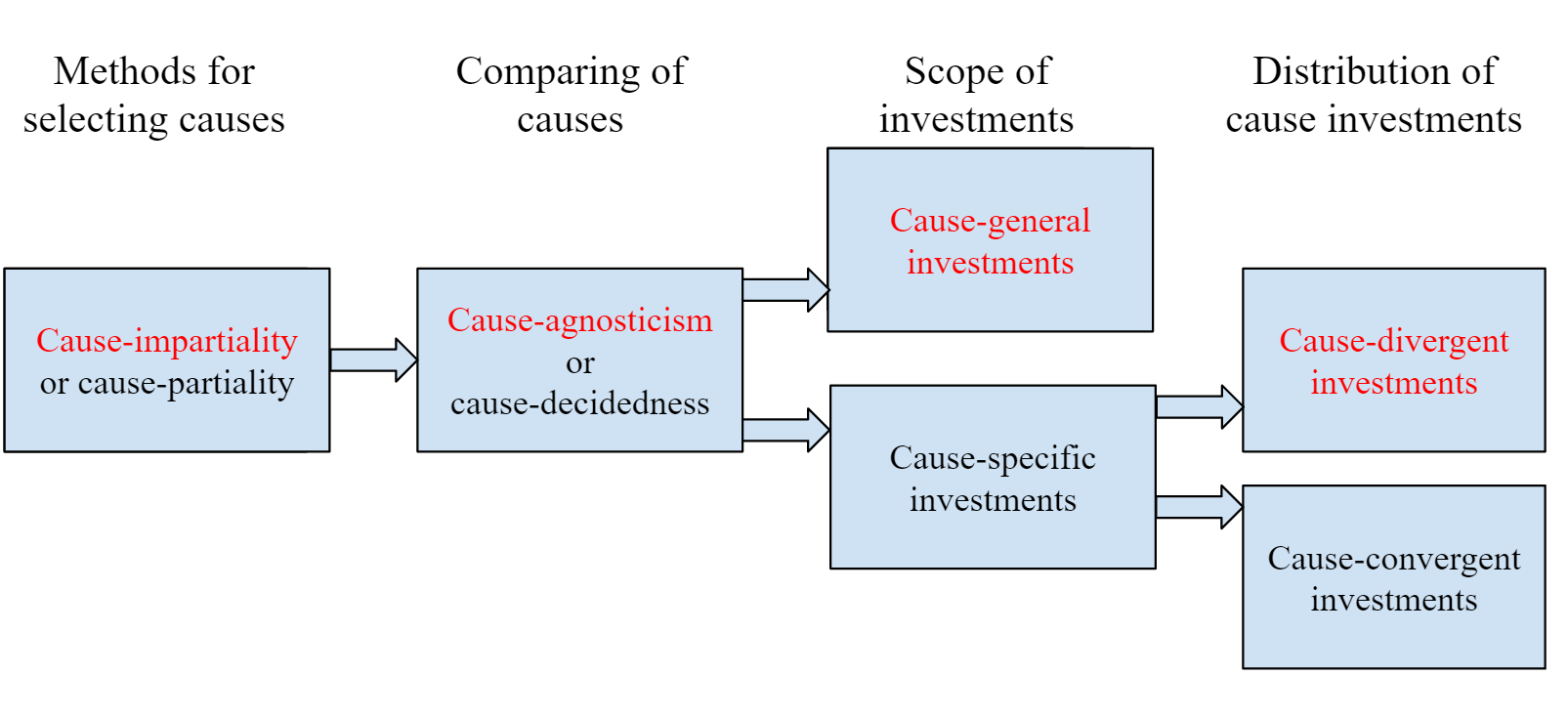

The term “cause-neutrality” has been used for at least four concepts. The first aim of this article is to define those concepts.

Cause-impartiality means to select causes based on impartial estimates of impact. This is the concept most frequently associated with the term “cause-neutrality”. Cause-impartiality can either be seen as entailing moral impartiality, or as pure means-impartiality: choosing the means (e.g., charity evaluation, policy work) to reach one’s moral ends impartially.

Cause-agnosticism means uncertainty about how investments (direct work, donations) in different causes compare in terms of impact.

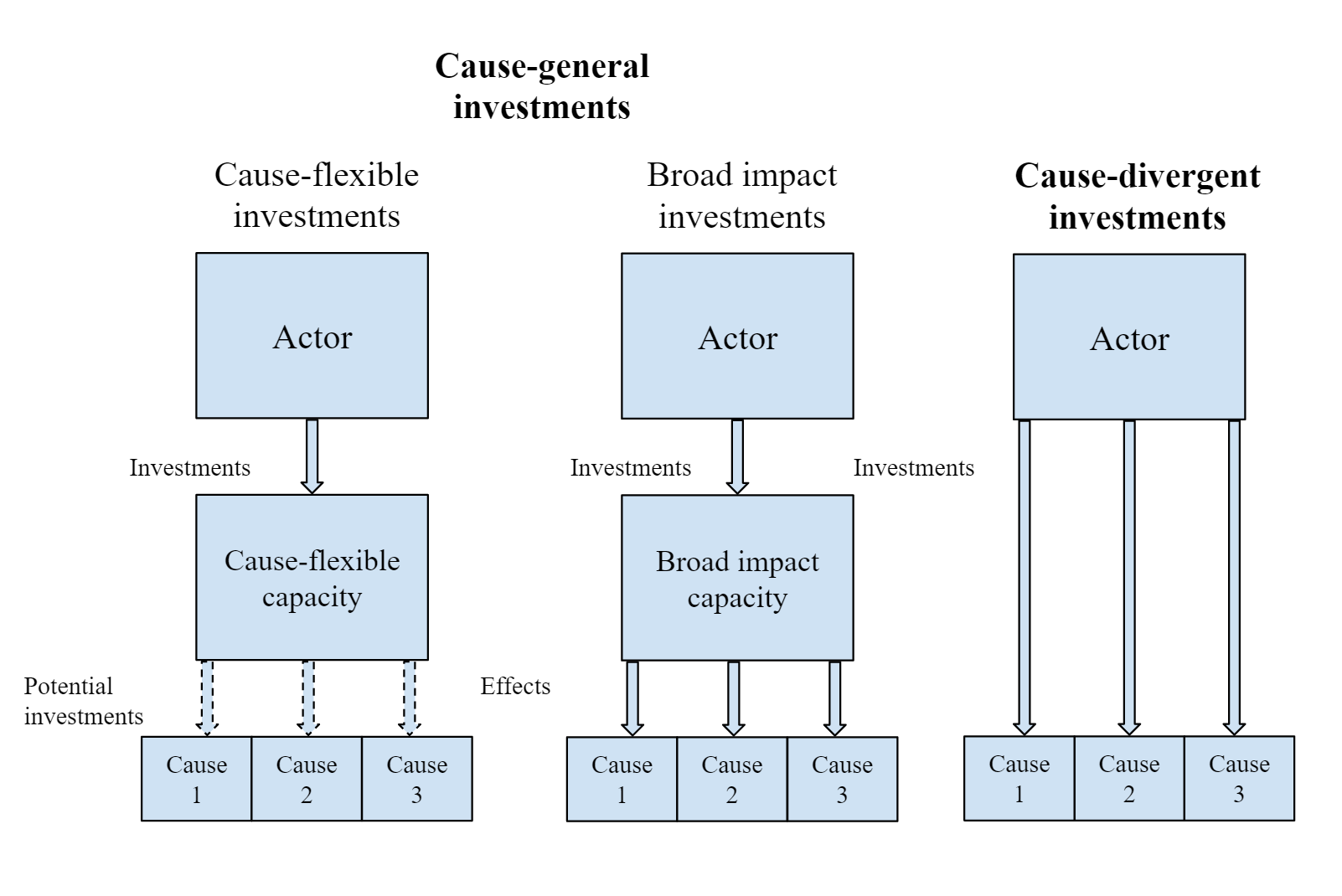

Cause-general investments have a wide scope. They yield capacity which can affect any cause. Cause-general capacity fall into two categories. Cause-flexible capacity (e.g., money) can be flexibly re-allocated across causes. Broad impact capacity (e.g., good epistemics) affect multiple causes without having to be re-directed.

Cause-divergent investments are cause-specific investments in multiple causes (e.g., global poverty, existential risk).

Figure 1: Decision process for altruistic investments (the four concepts’ antonyms in black).

My second aim is to give a survey of considerations on the value of cause-impartiality, cause-agnosticism, cause-generality, and cause-divergence. In these sections, I among other things discuss the relations between the four concepts.

Though cause-impartiality is sometimes mixed up with the other three concepts, it does not entail any of them. Cause-agnosticism can be a reason for cause-divergent and cause-general investments. Cause-divergent and cause-flexible investments can substitute for each other, whereas cause-divergent and broad impact investments can complement each other. Recruiting cause-impartial individuals amounts to a cause-flexible investment.

PDF version

Table of contents:2

Introduction

Cause-neutrality is often said to be a key feature of effective altruism.3 Despite that, it is not always clear what it means. One reason for that is that the term “cause-neutral” is sometimes used for multiple concepts.4 For instance, in the comments to Michelle Hutchinson’s post Giving What We Can is Cause Neutral, it seems to be used to refer to cause-impartiality, cause-divergence, and cause-generality.5 Similarly, in Anna Salamon’s post on CFAR and cause-neutrality, it seems to refer to cause-agnosticism and cause-generality.6

This means that defining and clarifying these concepts should be worthwhile. That is the first aim of this article.7

These concepts are also interesting in their own right. They have seen extensive discussion within the effective altruism movement. For instance, Holden Karnofsky (2016a) has discussed cause-divergence, and Peter Hurford has discussed cause-generality.

My second aim is therefore to further explore the four concepts: to show why they are valuable and how they are related. To that end, I give an overview of considerations for and against cause-impartiality, cause-agnosticism, cause-divergence, and cause-general investments.89 This overview is relatively substantial, and aims to deepen the discussion on these topics. For instance, it introduces a number of new concepts and distinctions. However, the considerations are still relatively tentative: I expect it to be possible to add more nuance to many of them. Hopefully they can serve as a stepping stone to further insights.

Four concepts

1. Cause-impartiality

Definition: To be cause-impartial is to select causes based on impartial estimates of impact.

Antonym: Cause-partiality. Currently, the term “cause-specificity” is sometimes used to express this concept. This may lead to confusion with cause-specific investments.10

Clarifying comments

Means-impartiality and moral impartiality. We may distinguish between means-impartiality and moral impartiality. Means-impartiality is impartiality regarding the means to one’s moral ends (e.g., charity evaluation, policy work). It is compatible with any set of moral ends, such as those defined by specific versions of utilitarianism, virtue ethics, etc. Moral impartiality (or ends-impartiality) is the notion that moral patients should be treated impartially. That is a key tenet of effective altruism.11 The most common understanding of the notion of cause-neutrality may be that it refers to the conjunction of means-impartiality and (the effective altruist understanding of) moral impartiality.12 An alternative understanding may be that the cause-neutrality notion refers to means-impartiality alone. Unless otherwise stated, my comments are intended to be compatible with both of these interpretations.

Decision rules. Means-impartiality is compatible with several different cause selection decision rules. One such decision rule is that we should maximize expected value. Another is that we should be risk averse: that we should put special weight on avoiding low-value outcomes. A third view is that there are side-constraints (e.g., rights) which we may not violate, even if doing so increases expected value. I talk of maximization of “impact” as a catch-all term for all of these decision rules. (Which of them are compatible with moral impartiality, and which of them to use, is outside the scope of this article.)

Moral impartiality in theory and in practice. It is possible to subscribe to moral impartiality in theory, yet fail to act in accordance with one’s ethical views in practice. For instance, someone may hold ethical views which entail prioritizing the global poor and still donate to a local charity for reasons of habit. Intuitively, we would not call such a person cause-impartial.

Impossibility of full cause-impartiality. It may in practice be impossible to reach full cause-impartiality,13 given what we know about human biases and our ability to assimilate large amounts of information. Full cause-impartiality should therefore not be seen as a feature of real flesh-and-blood actors, but it can be seen as an ideal to strive towards (cf. Helen Toner).

Attempted cause-impartiality. Attempted cause-impartiality means the use of methods intended to aid impartial comparison of causes, such as the ITN framework. Attempted cause-impartiality does not guarantee actual cause-impartiality. For instance, the ITN framework can be employed in a way which is partial to one’s favourite cause.14 Helen Toner has argued that it is honestly attempted cause-impartiality, rather than actual cause-impartiality, that is a key feature of effective altruism.

Sources of cause-partiality. Cause-impartiality is often contrasted with choices based on an emotional connection to a cause (see, e.g., Ben Kuhn 2014a). However, having an emotional connection to a cause is only one out of several possible sources of cause-partiality. Other possible sources include habits of supporting low-value causes (as we saw), measurement techniques which favour specific causes and, in the case of moral impartiality, moral views at odds with the effective altruist understanding of moral impartiality.

Considerations

Means-impartiality increases impact. Means-impartiality normally increases the impact of altruistic investments relative to a defined set of moral ends. If you do not select means to do good impartially, you may end up investing in a low-impact cause. You may also fail to change causes if it turns out that a new cause is more valuable than the one you had chosen to focus on. Means-impartiality could thus be seen as a corollary of the more general effective altruist principle that we should do the most good (cf. Ben Kuhn 2014b).

Petering out-argument. A common argument for cause-impartiality is that a cause-impartial movement will typically move on to a new cause once their focus cause has been solved. By contrast, a cause-partial movement may peter out when its favourite cause has been resolved (though this is not necessarily so).

Costs of reducing cause-partiality. Though reducing bias and other sources of cause-partiality normally carries benefits, it can also be costly. Beyond a certain point, the costs may outweigh the benefits.

Inhibition of growth. Since many potential recruits may not want to give up on their favourite cause, the effective altruism movement’s focus on cause-impartiality can inhibit growth (Ian David Moss 2016, 2017).

2. Cause-agnosticism

Definition: A cause-agnostic actor is uncertain about how different causes compare in terms of impact.151617

Antonym: Cause-decidedness.

Clarifying comments

Sources of impact. Since cause-agnosticism is defined in terms of impact, we should say a few things about the constitution of investment impact. These remarks will also be useful when we discuss cause-divergence and cause-generality. We may distinguish between the following sources of impact of investing in a cause.

Direct impact. An investment has a direct impact through furthering a solution to the cause.

Capacity-building. An investment can also have an impact through building capacity which increases the direct impact of later investments.

Option value. Option value is the value you obtain from having the option to change your strategy. Suppose that you have a default strategy, which you expect to follow in the absence of new relevant information. This strategy yields what we may call core impact. If you are able to change your default strategy in the light of new information, that may generate considerable additional value. This is called option value. Building capacity which allows for rapidly increased investment in a cause in the future can be an effective way of generating option value. (Cf. Holden Karnofsky 2016a.) Under high levels of uncertainty, having many options to change strategy can be very valuable.

Information value. Investing in a cause can yield information about the value of further investment in that cause (cf. Holden Karnofsky 2012). This generates information value. Information value can be very important under impact uncertainty.18

Cause-general impact. Investments in specific causes may also have cause-general benefits and costs as side effects. These side effects include methodological insights and other kinds of knowledge which could be applied to all causes (cf. Holden Karnofsky 2016a). They also include marketing benefits which accrue to the effective altruism movement as a whole (Peter Hurford). These effects affect all causes.19

Agnosticism about top causes. Cause-agnosticism primarily has to do with uncertainty about the relative impact of investments in the top causes. Someone who is certain of what the first, second, and third best causes are, but uncertain of how to rank other causes, we would not intuitively call cause-agnostic.

Cause-agnosticism resilience is the degree to which cause-agnosticism is expected to persist. If cause-agnosticism resilience is low, we expect to get a better sense of which causes have the greatest impact in the future.20

Considerations

Cause-impartiality and initial and eventual cause-agnosticism. If you are cause-impartial, you should arguably be cause-agnostic prior to having compared different causes. However, cause-impartiality does not entail that you should be cause-agnostic after having compared different causes.

Distribution of impact across causes. Cause-agnosticism is positively correlated with what may be termed impact-equality: multiple causes having roughly equal impact (as estimated). If two causes have roughly equal estimated impact, then small adjustments to our estimates may shift the order between them. That obviously increases the level of cause-agnosticism.

Conversely, if the distribution of impact across causes is heavy-tailed, as it is on many members of the effective altruism community’s estimates, then there is less reason to be cause-agnostic.

Epistemic deference, moral deference, moral cooperation, and moral uncertainty can all push in the direction of cause-agnosticism (cf. Holden Karnofsky 2016a).

Many epistemologists believe that we should defer to our epistemic peers (people who are as well-informed as ourselves). If my epistemic peers have a different view about some empirical question, I should adjust my credence in their direction. (What precise function to use is a difficult question, however.)

A more controversial position is that we also should defer to others’ views regarding moral questions. Two related issues are moral cooperation and moral uncertainty. Moral cooperation means to act in a way which increases others’ moral preference satisfaction, even if that could lead to lower moral preference satisfaction for yourself (i.e., you cooperate in prisoner’s dilemmas created by differences regarding moral preferences).21 It is in many ways functionally similar to moral deference. On moral uncertainty, many ethicists think that acting as if a particular ethical theory is absolutely certain is unwarranted. Instead we should assign some credence to several theories, and take theories other than our favourite one into account when we act. (Which function to use is an unsolved problem.)

Deference pushes you in the direction of your peers’ rankings of causes, under peer disagreement (i.e., if you rank causes differently in terms of impact from your peers).2223 This can lead to increased impact-equality, and thereby cause-agnosticism. It can also lead you to grow cause-decided of a new ranking of causes. If a sufficient majority of your most well-informed peers embrace a ranking different from your own, you may have reason to assign a high credence to it.

Moral cooperation does not in itself affect impact-equality and cause-agnosticism, but it can affect what we may call functional impact-equality and cause-agnosticism. Very roughly, moral cooperation makes you act as if you practiced moral deference, which by the preceding argument can affect impact-equality and cause-agnosticism under moral disagreement. Acting on moral uncertainty can push you in the direction of cause rankings entailed by moral theories other than your favourite one. By analogy with the preceding argument, this can affect impact-equality and cause-agnosticism.24

Time horizons. Some causes’ primary aim is to create moral value—e.g., by increasing happiness or reducing suffering—today, or in the near future. For other causes, the primary aim is to create moral value in the medium-to-long term future. The impact of the latter kind of causes is dependent on future events (including future investments) which may be difficult to predict. This means that a focus on the medium-to-long term future may be a reason for cause-agnosticism. Note also that information and option value may be particularly important if your time horizons are long.

Overconfidence. We are often biased towards overconfidence. Hence we might be biased against cause-agnosticism, and if so we should correct for that bias.

3. Cause-divergence

Definition: Cause-divergent investments are cause-specific investments in multiple causes. We may also use this term to describe capacities or actors. An alternative term for the last notion is “multi-cause actors” (antonym: “single-cause actors”).

Antonym: Cause-convergence.

Examples: The Open Philanthropy Project invests in multiple causes and is hence cause-divergent. The same holds true of the effective altruism movement as a whole. Animal Charity Evaluators and the Machine Intelligence Research Institute focus on single causes, and are thus cause-convergent. The same goes for a many non-EA movements, such as the feminist movement.

Clarifying comment

Though this is not the place to analyze this notion in much further detail,25 we may note that two important determinants of cause-divergence are the number of causes invested in and the proportion of investments going to causes other than the top cause.

Considerations 26

The question of whether to invest in multiple causes has been extensively discussed within the effective altruism movement (see, e.g., Holden Karnofsky 2016a). Also, much of the discussion on donations to multiple charities is relevant to this issue. Here are some of the more important considerations.27

Cause-impartiality and initial and eventual cause-divergence. If a cause-impartial group of people forms a movement, we might expect them to initially be cause-divergent. If they start studying different causes separately, they are likely to find evidence which support different causes. However, in the longer run cause-impartiality does not entail movement cause-divergence. For instance, if the distribution of impact across causes is heavy-tailed, then it may be that cause-impartial actors should converge on the top cause.

Diminishing marginal returns is a salient reason for cause-divergence (Holden Karnofsky 2016a). This reason is stronger under impact-equality (and thus normally also under cause-agnosticism, since they are correlated). If two causes have nearly the same impact, small amounts of investment may shift the order between them. Also, this reason is much stronger for larger actors, since such actors’ greater investments will make the marginal returns drop more substantially. This is a reason to think that the effective altruist movement should become more cause-divergent as its resources grows.

Value of specialization. For many individuals and small organizations, it can be overly costly to acquire requisite cause-specific knowledge in more than one cause. Instead the most efficient strategy is normally to be cause-convergent. Donations is another matter, since there small actors can often rely on expert advice—they do not have to acquire extensive cause-specific knowledge of their own. Hence this is normally not nearly as strong a reason for cause-convergence regarding donations as it is regarding direct work.

Value of coordination (cf. Ben Todd 2016, Daniel May). Different donors trying to second-guess where other donors are going to give, in order to maximize marginal returns, can carry large costs for the effective altruism movement. Hence it may be better if members of the effective altruism movement promote and follow a norm where they diversify their donations in the direction of their ideal basket of donations from the whole movement. On this argument, donors should give to causes they find important, even if they believe that other members of the movement may decide to fund those causes later on.28

Cause-agnosticism, cause-divergence, information value, and option value. Under low-resilience cause-agnosticism, option value and information value are highly important considerations.29 For most causes, the marginal information value of additional investments is likely to be rapidly diminishing. Similarly, for most causes the marginal option value of additional capacity-building investments is likely to be quite rapidly diminishing. This means that cause-agnosticism can be a reason for cause-divergence. To see that, suppose that you believe that cause A has higher impact (excluding information value) than cause B, but that you are uncertain of that, because you are uncertain of both causes’ levels of impact. Then it might be worth making some investment in B for information value reasons. Similar comments apply to option value. (Cf. Holden Karnofsky 2016a.)

On the other hand, investments in causes with great possible impact and high levels of uncertainty (e.g., AI risk) can generate much more option value and information value than investments in most other causes. That means that information value and option value considerations can under certain assumptions point to cause-convergence rather than cause-divergence.30

Cause-general impact of cause-specific investments. The cause-general benefits of investments in a specific cause probably often only correlate weakly (or even negatively) with the cause-specific benefits. For instance, we saw that investing in a specific cause can give cause-general methodological insights. However, there is little reason to believe that such methodological insights are generally much more frequent in high-impact causes than in low-impact causes. Also, the number and value of such insights is probably rapidly diminishing with additional investments into a cause. Similar comments apply to many other kinds of cause-general side effects of cause-specific investments. Hence taking such side effects into account can be a reason for cause-divergence.

Risk aversion. It could be argued that cause-agnosticism and risk aversion together form a reason for cause-divergence. Under cause-agnosticism, cause-divergent investments increase the chances that at least some of your investments further the top cause. However, it could also be argued that risk aversion is a reason to be cause-convergent towards the cause where the price of failing is the highest (e.g., existential risk reduction).

Personal fit. Some people having a poor personal fit regarding the top cause can lead to cause-divergence. However, if the best cause has sufficiently high impact, that may trump personal fit considerations.

Suspicious convergence and divergence. Gregory Lewis has argued that convergence of all of our considerations on a particular cause can be suspicious. He suggests that this may be explained by a bias of some form, such as confirmation bias. What about divergence and convergence of investments across different people? Both of them may have suspicious explanations. Cause-divergence may be due to supposedly cause-impartial members of the effective altruism movement hanging on to the their favourite causes in the face of evidence saying that other causes have higher impact. Similarly, cause-convergence may be explained by group-think.

4. Cause-generality

Definition: Cause-general investment have a wide scope: they can affect any cause. We may also use this term to describe capacities or actors.31

Antonym: Cause-specific investments.

Examples: Recruitment to a cause-impartial movement constitutes a cause-general investment. Other examples are improving the effective altruism movement’s epistemics and building institutions for allocating resources across causes (such as 80,000 Hours’ coaching service). Examples of cause-specific investments include AI safety research and developing connections within the AI community.

The Centre for Effective Altruism is a paradigmatic example of a cause-general organization, whereas the Machine Intelligence Research Institute is a paradigmatic example of an organization which focuses on cause-specific investments. The Open Philanthropy Project is a more complicated case. While most of their investments are cause-specific, the fact that they invest in so many causes means that their work arguably generates substantial cause-general benefits as side effects. They also make cause-general investments into, e.g., studies of various methodological questions.

Clarifying comments

Cause-flexible capacities and broad impact capacities. Many cause-general capacities are cause-flexible, meaning that they can be re-directed across causes. Examples include funding and staff with general purpose skills. Another kind of cause-general capacities are the broad impact capacities.32 They have positive effects on multiple causes without having to be re-directed. Examples include good effective altruist epistemics and reputational benefits which organizations acquire through being part of the effective altruism movement.

Figure 2: Cause-general vs. cause-divergent investments.

Cause-generality as meta.The term “meta-level” is often used for the cause-generality concept (Peter Hurford, Rohin Shah). However, the term “meta-level” is often used for other concepts as well (it deserves a clarifying analysis of its own).

Cause-impartiality as a source of cause-flexible capacity. Cause-impartial members of the effective altruism movement constitute cause-flexible, and hence cause-general, capacity (to at least some degree; see next comment). Partly for this reason, effective altruism is closely associated with the notion of cause-general capacity.

Cause-generality is a matter of degree.33 An example which illustrates that is a cause-impartial individual who has invested in acquiring knowledge relevant to AI safety. The fact that they in principle are open to investing in other causes means that they to some extent constitute cause-flexible capacity. On the other hand, the fact that they have invested in capacity which is not easily transferable to other causes pulls in the direction of cause-specificity. There are also investments which are neither fully broad impact nor fully cause-specific. They include investments in improved epistemics which are especially targeted at epistemic problems in a certain cause, such as AI safety.34

Considerations

The value of cause-general investments has seen substantial discussion within the effective altruism movement (see, e.g., Peter Hurford, Rohin Shah, Ben Todd 2015). Here are some of the more important considerations. I will start with considerations relevant to both cause-flexible and broad impact investments, before turning to considerations unique to each of these classes of investments.

Cause-impartiality and cause-generality. Cause-impartiality does not entail that we should make cause-general investments. For instance, if we are sure that one cause has the highest impact, it may be more effective to exclusively make cause-specific investments into that cause. Note, though, that some forms of cause-general investments—e.g., in cause prioritization research—can increase the level of cause-impartiality.

Growth of cause-general capacity. A key question is how much cause-general capacity a given investment translates into. If we, e.g., can grow the effective altruism movement relatively fast at little cost, that can be a reason to focus on building that kind of cause-general capacity.

Effectiveness of cause-general capacity towards individual causes. Another key question is how effective cause-general capacity is towards individual causes compared to cause-specific investments. (Several of the below comments also relate to this issue.) If cause-general capacity does not have a large impact on individual causes, then having substantial cause-general capacity may not be that useful after all (cf. Peter Hurford and Rohin Shah). This question should be studied further. In particular, we should study the value of particular kinds of cause-general capacity. The “meta” notion is often associated with effective altruism movement growth, but there are many other kinds of cause-general capacity, including improved epistemics and improved organizational skills.35 It is hard to make general statements about the effectiveness of all these kinds of capacity.

Cause-general work can also have negative effects. This is especially true of cause-general work on effective altruism movement growth (cf. Jeff Kaufman on Intentional Insights). It may therefore be especially important that that kind of cause-general work is carried out by highly competent and responsible actors.

Cause-general side effects of cause-specific investments should be taken into account. We saw above that cause-specific investments could have positive cause-general effects, e.g., in the form of marketing benefits. But they can also have negative cause-general effects (though probably more rarely so). Work on controversial causes—including many political causes, certain technologies, etc.—can reflect badly on the whole effective altruism movement (depending on how the work is branded). It is therefore important that that kind of sensitive work, too, is allocated to especially competent and responsible actors.

Information value. Both cause-specific and cause-general investments can yield information value, but it is hard to say anything general on this issue. Instead, we need to compare the information value of particular cause-specific and cause-general investments.

The value of cause-flexible investments

Cause-agnosticism and option value. Cause-flexibility creates the option to switch away from the default strategy at relatively low cost. The more cause-agnostic you are, the more valuable this option normally is (conditional on the level of cause-agnosticism resilience not being very high). Hence cause-agnosticism can be a reason for cause-flexible investments. Cause-flexible capacity can also be very useful if you expect to find new, currently unknown, causes in the future.

However, some argue that cause-specific investments may be a more effective way of generating option value (cf. Howie Lempel). Also, as we saw, most of the option value may come from one or a small number of causes. If that is right, it may be better to invest in them directly.

Substitutability with cause-divergent investments. The value of cause-flexible investments tends to correlate with the value of cause-divergent investments. Both are more valuable under cause-agnosticism. Hence cause-flexible and cause-divergent investments are to some extent substitutes for each other. If your investments span many causes, it becomes less important to have capacities which can be re-allocated across causes (and vice versa). How to prioritize between these two strategies is an important and understudied question.

Transformation costs. Many kinds of cause-flexible capacity can only be used towards specific causes after a transformation period (e.g., to re-train individuals with general purpose skills). The greater the associated transformation costs are, the greater the reason to make cause-specific investments directly is (cf. Howie Lempel).

Time horizons. The transformation period normally delays your investment’s effects on specific causes. That means that the more urgent investments in specific causes are, the less we should focus on cause-flexible investments. Conversely, cause-flexible investments may be more valuable if you think that most of the value of the effective altruism movement lies decades ahead, since it is very likely that we will want to change our strategy very substantially over the years under such scenarios.

The value of broad impact investments

Broad impact investments and cause-divergence. Many capacity-building investments increase the effectiveness of other investments. Examples include both broad impact investments such as improved effective altruist epistemics and cause-specific investments such as AI strategy research. It is normally more valuable to have such capacity-building investments be broad impact investments under cause-divergence than under cause-convergence. (Since cause-agnosticism is a reason for cause-divergence, this means that cause-agnosticism is normally a reason for such broad impact investments as well.)

To see that, suppose that we want to increase the effectiveness of all our investments. We can do this either by investing in relevant broad impact capacity, or by investing in relevant cause-specific capacity in the causes we have invested in. The more causes we have invested in, the more expensive the cause-specific approach will normally be, and the more reason we have to go for the broad impact approach. Hence it is natural that the Open Philanthropy Project invests in broad impact capacity. It also follows that if the effective altruism movement keeps adding more causes, due to diminishing marginal returns, it may be well-advised to increase its broad impact investments.

Conversely, if you have substantial broad impact capacity, that may facilitate expansion into new causes, due to economies of scope. Hence broad impact investments and cause-divergence may support each other.

Cause-neutrality bibliography

Drescher, Denis (2014). Introduction to Effective Altruism.

Hurford, Peter (2015). EA risks falling into a “meta trap”. But we can avoid it.

Hutchinson, Michelle (2014). Should Giving What We Can change its pledge?

Hutchinson, Michelle (2016). Giving What We Can is Cause-Neutral.

Karnofsky, Holden (2012). Our top charities for the 2012 giving season.

Karnofsky, Holden (2016a). Worldview Diversification.

Karnofsky, Holden (2016b). Hits-based giving.

Kuhn, Ben (2014a). Effective altruism reading material for busy people.

Kuhn, Ben (2014b). How many causes should you give to?

Lempel, Howie (2016). Comment on Rohin Shah’s “Thoughts on the “Meta Trap”.

Lewis, Gregory (2016). Beware surprising and suspicious convergence.

May, Daniel (2016). Should you donate to multiple charities?

Moss, Ian David. (2016). All causes are EA causes.

Moss, Ian David (2017). In Defence of Pet Causes.

Salamon, Anna (2016). Further discussion of CFAR’s focus on AI safety, and the good things folks wanted from “cause neutrality”.

Sentience Politics. The Benefits of Cause-Neutrality.

Shah, Rohin (2016). Thoughts on the “Meta Trap”.

Todd, Ben (2015). Why we need more meta.

Todd, Ben (2016). The Value of Coordination.

Toner, Helen (2014). Effective altruism is a Question (not an ideology).

- This article benefitted from comments from Harri Besceli, Owen Cotton-Barratt, Max Dalton, Ben Garfinkel, John Halstead, Michelle Hutchinson, Gregory Lewis, Michael Page, and Claire Zabel. Thanks also to Oge Nnadi for help with the editing.↩

- The reason cause-divergence comes before cause-generality even though cause-generality appears first of two in figure 1 is that cause-generality is a more logically complicated notion than cause-divergence.↩

- The term “cause” does not have a crisp meaning, and deserves further analysis. The present analysis is intended to be compatible with the standard interpretations. (See Owen Cotton-Barratt.) For instance, existential risk could be seen as a cause, but you could also cut the cake so that individual existential risks become causes of their own.↩

- All of them are associated with “equality” between causes, in some sense.↩

- Hutchinson primarily uses the term to refer to cause-impartiality. However, she also implies that Giving What We Can constitutes cause-general capacity, in that Giving What We Can pledgers are not expected to exclusively donate to global poverty charities (cf. the section on cause-generality). (Cf. also her post from 2014 on the same topic, where the term “cause-neutral” is primarily used in the cause-generality sense.) One of the commentators seems to think that cause-divergence is a necessary condition for cause-neutrality, however. “If cause-neutrality is ‘choos[ing] who to help by how much they can help‘, then there are many individuals and organizations who seem to fit that definition who I wouldn’t ordinarily think of as cause-neutral. For example, many are focused exclusively on global health; many others are focused on animals; etc.”↩

- Salamon argues that CFAR cannot be “cause-neutral” (note the scare quotes), if that means that they should “[a]ppear to have no viewpoints, in hopes of attracting people who don’t trust those with our viewpoints”. Here she seems to say that CFAR should not claim to be cause-agnostic. She also argues that CFAR cannot “emphasize all rationality use cases evenly” but that they should focus on those relevant to AI safety. This means that she thinks that CFAR’s investments should not be cause-general (or at least not fully so), but rather relatively cause-specific.↩

- Note, though, that my definitions are more similar to dictionary entries than to fully fledged philosophical analyses. Note also that the conceptualization of these issues presented here is provisionary. It is part of a larger project of revision and explication of key effective altruist concepts that the CEA research team is undertaking. Some of the analysis presented here may be affected by work on other concepts (e.g., cause).↩

- Unless otherwise stated, my comments on the value of investments relate to both direct work and donations.↩

- There are relevant analogies between cause selection and intervention selection. In analogy with cause-impartiality, we may define intervention-impartiality as selecting interventions within a cause based on impartial estimates of impact. We may define notions of intervention-agnosticism, intervention-divergence, and intervention-generality analogously. My comments on cause-impartiality, cause-agnosticism, cause-divergence, and cause-generality pertain to those concepts as well.↩

- Cf. Ian David Moss’s post All causes are EA causes and Michael Dickens’s comment on that post.↩

- However, there is no consensus within the effective altruism movement on precisely what moral impartiality entails. To just take one example, a difficult question is what moral impartiality entails with respect to non-human animals.↩

- Hence it might be argued that we should use the term “cause-neutrality” for this notion. I have chosen not to do so, in order not to confuse my own suggested concepts (“analysans”) with the pre-theoretical concept I am trying to analyze (“analysandum”).↩

- All four distinctions should be seen as matters of degree, rather than as either-or-dichotomies.↩

- One could also talk about ostensible cause-impartiality for uses of the ITN framework which do not in fact constitute honest attempts to treat all causes impartially. Cf. the discussion on evidence-based policy vs. policy-based evidence.↩

- Actors include both individuals and organizations and movements.↩

- The impact of an actor’s investments in a cause is partially dependent on that actor’s talents and knowledge: what within the effective altruism movement is usually called personal fit. (This is especially true of direct work.) An important notion is what we may term “actor-independent impact”. This is the impact of investing in a cause, given the personal fit of a hypothesized average actor (i.e., you “subtract personal fit”). One can be cause-agnostic both regarding the “actor-dependent” impact of a particular actor’s investments (including one’s own) in different causes, and regarding the actor-independent impact of investments in different causes. Most of my comments pertain to both of these concepts. When that is not the case it should be clear from the context. (Ben Garfinkel emphasized this distinction.)↩

- There are typically multiple interventions which can further a cause. This raises the question of what intervention’s impact equals the “cause impact”. For an actor estimating the impact of their own investments in a cause, the relevant intervention is that which they think has the greatest impact if pursued by them. Actor-independent cause impact (see the preceding endnote) is the impact of the intervention which has the greatest impact if we subtract personal fit. (Ben Garfinkel emphasized this distinction.)↩

- The concepts of information value and option value are closely related. Cf. Hanemann (1989).↩

- Cause-general impact can also be divided into several categories, such as capacity-building and information value.↩

- Gregory Lewis emphasized this notion.↩

- Moral trade is a kind of moral cooperation, where the parties agree to cooperate on certain terms.↩

- This paragraph and the next one have been edited following comments by John Halstead.↩

- If your peers agree with you on your current ranking, you may rather increase your credence in it. Hence cause-agnosticism may be reduced.↩

- Note that on some views on how to resolve moral uncertainty, certain moral theories can end up dominating your decisions even if you assign a small credence to them. For instance, Hilary Greaves and Toby Ord have argued that the most plausible approach to moral uncertainty in population ethics “systematically pushes one towards choosing the option preferred by the Total and Critical Level views, even if one’s credence in those theories is low”. Thanks to John Halstead for prompting this comment.↩

- Cf. endnote 7.↩

- This section, and the corresponding section on cause-generality, benefitted greatly from Gregory Lewis’s comments.↩

- To make further progress on these questions, it may be wise to zoom in more on specific causes. For instance, someone thinking that AI risk is the top cause could reflect on whether the effective altruism movement’s investments should converge on AI risk, or whether they should diverge across a number of (specified) causes.↩

- I owe this consideration to Owen Cotton-Barratt.↩

- They are less important under cause-decidedness and high-resilience cause-agnosticism, since then you do not expect new information to shift your cause priorities.↩

- The fact that some causes can generate much more information value and option value than others means that the information value and option value considerations cannot be used as a blanket argument for cause-divergence. Instead, whether specific causes merit investments for reasons of information value and option value must be decided on a cause-by-cause basis.↩

- I use the capacity sense frequently below.↩

- Potentially, these concepts could be subsumed under existing concepts from management or economics. Tips to that effect would be appreciated.↩

- As we saw above, the same goes for cause-impartiality, cause-agnosticism, and cause-divergence.↩

- Cf. endnote 6.↩

- As we saw above, the term “meta” is also used for other concepts altogether, such as donation advice and other methods for increasing the impact of other people’s investments.↩