Articles

Charity Entrepreneurship

Charity Entrepreneurship

Want to start a high-impact charity? It’s not an easy job, but it can be an incredible way to have an impact. In this talk from EA Global 2018: London, Joey Savoie discusses the pros and cons of founding a charity. He also describes what his organization, Charity Entrepreneurship, can do to help would-be founders get started.

A transcript of Joey's talk is below, which has been lightly edited for clarity. You can share your thoughts about this talk on the EA Forum.

The Talk

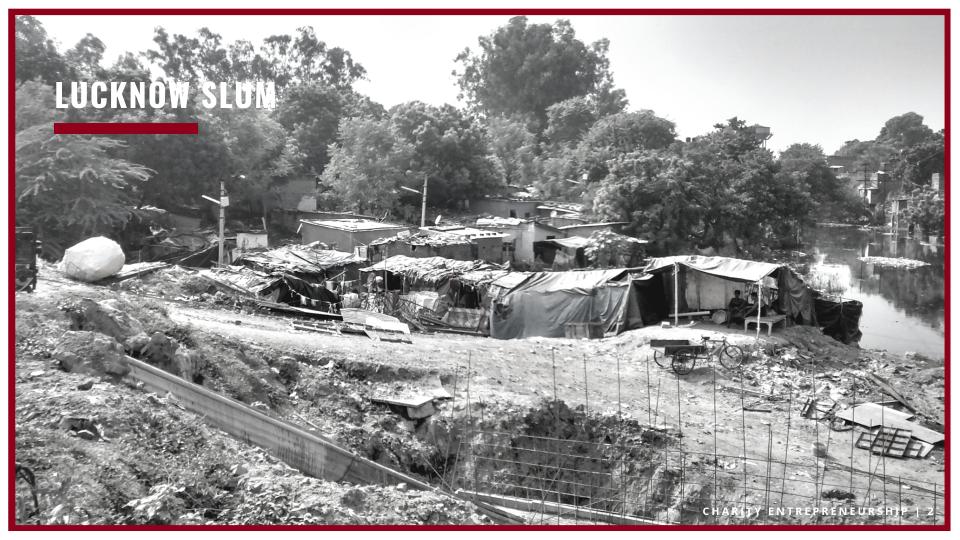

So, we are going to talk about charity entrepreneurship. But first, I'm going to take you to a slum of Lucknow.

Lucknow is a city in India, and this picture is fairly representative of the state of affairs. You can tell from the picture that there are giant health and poverty concerns. It really is a place where charitable intervention can make a huge difference. One thing you can't tell from this picture, though, is the sheer size of this slum. A team of SMS Vaccine reminding staff went from building to building trying to find pregnant mothers, and it took hours to cover even a small section of this slum.

But of course that is just one slum in a much larger city. Lucknow city has several hundred slums, 200 to 300 slums by the record right now. Each of them has a unique set of problems, although there are some commonalities in terms of global health and economic difficulties. There's a huge volume of good that can be done in a city like Lucknow.

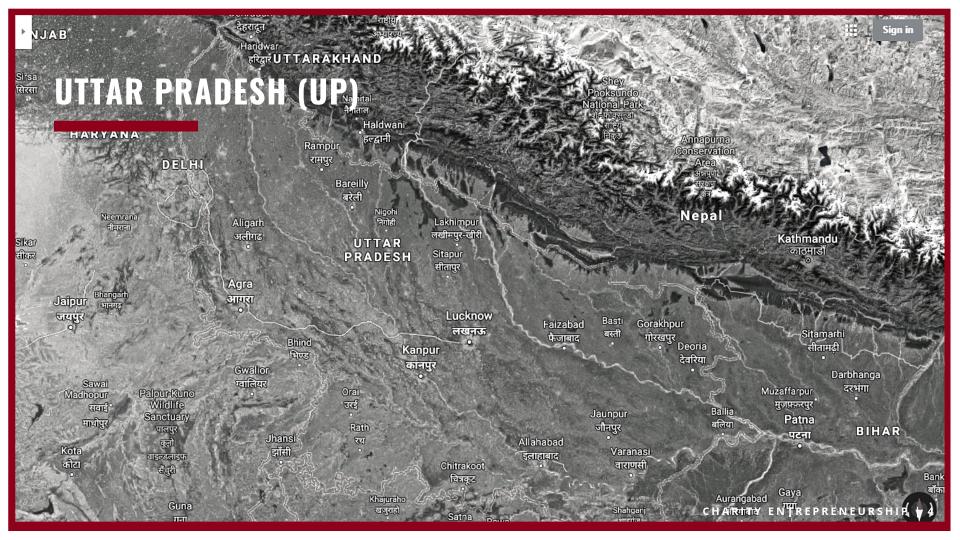

But of course we can zoom out further, and look at Uttar Pradesh. This is a state in India, but it is such a big state that if it were a country it'd be the sixth largest country in the world. It truly is massive. You could have a giant organization spend their entire budget and all their staff time all working in Uttar Pradesh, and not even make a dent in the massive scale problems that they have, both from poverty and other sorts of issues.

But of course, we can zoom out even further and look at India. A country with over a billion people, and problems to match. Although there are incredible charities working there, there's still a huge need for more organizations working intelligently, systematically, and with evidence.

Of course, India is not the only country with problems, and of course, global poverty isn't the only problem. There's tons of different issues that one can work on, like animal welfare, mental health challenges, economic development, or migration. There are a lot of gaps in the world where new and effective organizations could be founded.

Why I'm talking about these gaps is because I think that a lot of people are under the impression that there's already a ton of charities out there. Maybe all the best opportunities have been filled by organizations, and that's really not the case. There really is room for fantastic new charities to be founded and be fantastically high impact.

I'm going to talk about why charity entrepreneurship is important. I'll talk about its importance to the world, and to the EA movement specifically. I'll also talk about who charity entrepreneurship might be a good fit for; it really is not a good fit for everybody. Some people are fantastically well aligned and do a really good job, while other people aren't a good career fit and shouldn't enter the space. Finally, I'll address how Charity Science is aiming to help new charities get founded and started off on the right foot.

I'm going to make this argument from more of a cluster thinking perspective than a sequence thinking perspective, which means coming at it from a bunch of different angles and showing that charity entrepreneurship looks very good and very high impact from several different perspectives.

The first thing that comes to almost everyone's mind when they think about the potential impact of charity entrepreneurship, is the sheer size of good that you can do when you found a successful charity.

Here's some of the money moved from some top GiveWell recommended charities. You can see it's often in the 10s of millions of dollars. And these are just the numbers from GiveWell itself, as opposed to the total money that's going towards each charity.

Suffice to say that starting a high-impact charity can redirect millions of dollars in a positive direction. So, even if your charity is only 1% more effective than the charity that a donor would have given to otherwise, it can have a really massive impact just because of the sheer volume of money.

There's also a force multiplication argument about this. You're not just directing money, when you're founding a new charity. You're directing talent, you're directing interest, you're directing passion towards your chosen issue. There are a lot of people who will work for a high-impact charity, but wouldn't ever found one themselves. By creating a new high-impact charity, you're creating an opportunity for talented individuals to get invested in the field and to make a difference.

Finally, there are hits. So, everyone wants their charity to be successful, and charity entrepreneurship is inherently, like normal entrepreneurship, a risky business. A lot of charities will be started and the impact analysis will come back bad, or the charity won't have a valid way of scaling. There's a lot of ways to fail, but there's also a lot of ways to have massive success. Success that is incomparable to many other jobs. For example, a minor hit, although it feels funny to call it a minor hit, would be becoming a GiveWell recommended charity. Just a small percentage difference between you and the other GiveWell recommended charities in terms of being better, or even simply giving more options that GiveWell can recommend to attract donors from different spaces and different interests. So a minor hit can make a huge difference.

But that's not even taking into account the major hits. Most giant charitable organizations that are around today started off as a small group. The benefits of an EA group being the group to start the next Oxfam, and shaping an entire cause area, is truly massive.

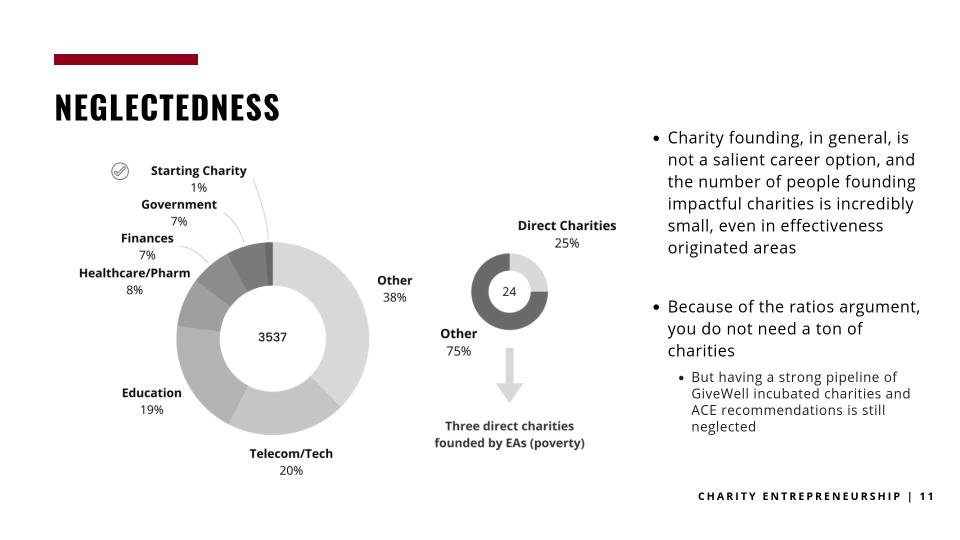

The next thing I want to talk about is neglectedness. Charity Entrepreneurship isn't a salient career path for a lot of people. Many people will have considered entrepreneurship as a career path, and many, many people will consider working for a charity. But founding a charity is off the radar, even in EA. So, this chart shows is the percent of people working in different jobs from the EA survey that was most recently conducted. Several thousand people responded, and an incredibly small number of them have seriously considered founding high impact charities. Of those who have, almost all of them have been in global poverty. For example, organizations like New Incentives, Charity Science Health, or Fortify Health. So there's a truly large opportunity for more people to get involved in the space, more people to work in the space, and eventually for people to start high impact organizations.

The next thing we'll talk about is tractability and track record. Founding a charity is a difficult job, especially one good enough to be a GiveWell or Animal Charity Evaluators recommended charity, but it's not impossible. Some of our collective track record shows this. A lot of the charities we view as strongest and most impactful in the EA movement, weren't started by someone with 55 years of experience in the relevant area. They were instead started by someone who came into it with more of an analytical mindset, more of an EA mindset, someone looking for cost effectiveness or evidence base.

A lot of the recent charities that have been started and that have become GiveWell incubated, were coming with the same mindset. That's a huge competitive advantage over other charities that happened to be cost-effective by luck, as opposed to explicitly seeking cost-effectiveness out or trying to maximize it.

No good EA presentation would be complete without an expected value calculation. So what's the numerical worth of Charity Entrepreneurship? Well, there are a couple different calculations. Peter Hurford's calculation assumes an 85% chance that the charity has zero impact, so fails completely, and assumes a 15% chance of becoming GiveWell recommended. These numbers were based off Charity Science Health, the charity that we founded, after doing a similar round of analytical research to the ones that we now do for all sorts of charities.

His model determined that the average staff member would be worth $400,000 of equivalent donations to high impact charity. That's just the average staff member, that wasn't for co-founders or the founding team in particular. This is an incredibly high impact thing. This is $400,000 donated. So, even if you earned $400,000 you'd have to donate 100% of it to match this level of impact. We did an internal model that was a bit more pessimistic, assuming that there's only a certain chance that someone would get to the point where Charity Science Health has got, and get GiveWell incubated, and ended up at a similar figure of $200,000 of expected value of donations.

This sort of impact is really, really high, and these calculations are quite conservative relative to a lot of the other impact estimates going around the EA movement.

There's a whole bunch of other benefits that I'd love to spend more time on. But I'm going to go through really quickly because we only have so much time. The first one is skill building. So, entrepreneurship gives you an opportunity to try on a lot of different hats. That's part of why it's hard and intimidating, but it also gives you a chance to build a lot of different skills. If you try to found a charity, even if you fail, going into the next job having basic budgeting skills, fundraising skills, management skills, hiring skills, it gives you a huge advantage and will stick with you for a long time.

Similarly, career capital. If someone sees that you took a good attempt at a project, even if it's a failed project, but especially if it's successful project, that does wonders for your CV and career capital in general. You can use a successful charity as a stepping stone towards getting into a high impact position with the World Health Organization, or any sort of other organization that would look at that sort of thing.

The next thing is attributable impact. So, calculating the impact that you're going to have is really, really difficult, and there's one less step you have to calculate with charity entrepreneurship. If you do, in fact, start a charity that no one else would have founded, that wouldn't have gotten started without your time and energy put into it, what you're most looking at is that charity's impact as a whole. Instead of having to calculate both the organization's impact, and then your specific impact within the organization. When calculating your impact in othre cases, maybe the organization is great, but your personal role is very minor. Or maybe your staff impact is big, but the organization sucks. With charity entrepreneurship, you only have to calculate the organization's impact.

Job satisfaction is the next one. As I said, it's really not the perfect fit for everybody, and we'll go a little bit more into that soon. But for the right personality type, it's incredibly enjoyable. Being able to look at your charity and know that you built it from scratch, being able to work with flexible hours, with a bunch of different staff. There are a lot of benefits to it. There's an unparalleled amount of job diversity. But there are also cons. Ambiguity is tough, which is a thing you're going to have to deal with as a charity entrepreneur.

Not only are there personal benefits for founders, there are also benefits to the EA movement in general. Charity entrepreneurship enhances movement growth, by expanding the EA movement outside of its traditional sphere. By getting involved at the charity level and hiring people in that field, working with people who, say, work in vaccinations, you expand EA in a very concrete way to a sympathetic audience.

There's also a much clearer case for impact for some of these charities. It's fine to go and tell someone that you're doing a philosophy think tank that will eventually save humanity, but it sure is nice to also be able to say we started a vaccine charity that people think is highly cost effective. That sort of concrete case for impact can benefit the whole EA movement, in terms of showing that we are in fact doing what we say we're doing and having success doing that.

The next thing is stability. Organizations tend to outlive movements. The EA movement is social movement, and it is fragile in many ways. It gets stronger the more organizations there are to anchor it, and tie it to reality in a long lasting way.

Finally, opportunities. Lots of EAs want to work for EA organizations. Lots of EAs wants to work for high impact jobs. As I mentioned with the force multiplier before, by creating an opportunity, you create space for people to grow, develop their capacities, and expand the EA movement. It gives a space for people to go once they get involved.

Next up, community learning value. Even a failed project can be massively impactful if you get a lot of learning value from it. One of our early projects didn't work at all, but we were able to publish a giant report explaining why it didn't work and tens of other organizations in the EA movement were able to learn from that mistake and not repeat the same thing. If your charity does fail, and you are able to be transparent about why it failed, and you learn from it, you can benefit not only the charity entrepreneurship community within EA, but the broader EA movement as a whole, because a lot of these lessons are generalizable.

Finally, there's inspiration. If you can inspire someone else to found a charity through your example, that can be massively high impact. If people can see other people doing successful, ambitious projects, then it can lead to precedence. So for instance, we saw New Incentives do a really great job founding their charity, and that gave us confidence to start Charity Science Health. Charity Science Health gave Fortify Health confidence to do that, and now Fortify Health, New Incentives and Charity Science Health can give other EAs a chance to look at charities that have been successful and it gives them a chance to feel inspired by the possibility.

The next thing is passive impact. So, for people who have heard of passive income, passive impact is a very similar concept. Basically, if you set up a charity to run independently without you, and it continues to do good in the world, you continue to hold some sort of counterfactual responsibility for that impact.

The last thing that I'll talk about briefly is just the room for more funding. Room for more funding isn't a huge impact if it's filled by someone who's otherwise going to donate to a fantastic charity, but by creating a new charity, you can leave a lot of room for new donors to get involved, and donate to maybe something particular to their interest, while still making a really high impact.

So why now? There's a lot of reasons why founding a charity now in particular is maybe a lot better than historically. Hopefully, it will continue to be this good in the future. There's a lot of funder support and funder interest in this sort of thing. The GiveWell incubation program has been trying to fund programs that might eventually become GiveWell top charities. Animal Charity Evaluators has money for this, Open Philanthropy is very interested in new charities and of course, Charity Science, my organization, provides seed funding to new projects starting up. Just an unparalleled time where funding probably won't be the major bottleneck for a lot of charities being founded, if they are founded in an evidence-based way in an evidence-based cause.

There's also mentorship support. You're not the first charity working on this anymore. So you are able to kind of connect with an alumni community. Charities that we've talked to have shared hiring pools and strategies for management and all sorts of different things. The EA community really is starting to build up a network of people you could talk to about issues, whether it's communications or research, and really get an informed perspective of someone who's done something quite similar, quite recently.

Finally, there's still gaps. That's why I talked about one specific case at the beginning. It's really, really easy to forget just how big the world is, and just how large-scale our problems are. There's a ton of malaria charities, and yet, there's still malaria, killing hundreds of thousands of people every year. There's still a lot of work to be done, and the EA movement can contribute a lot more to that. Specifically, there are even lists of ideas that people would like to see more of. GiveWell has a list of priority programs that has 25 ideas. ACE has a list of charities that it would like to see, with 17 ideas. Charity Science Entrepreneurship, we want to do a research program that recommends two to five ideas every single year, that'll be particularly promising to found, in the GiveWell priority program ballpark, or even more high impact, like something that could compete with AMF.

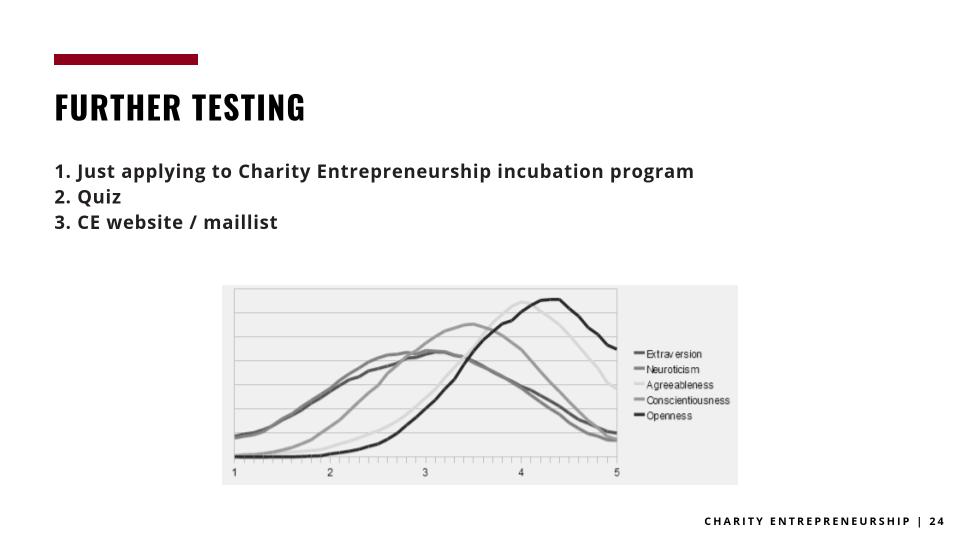

So I want to talk a little bit about who Charity Entrepreneurship is a good fit for. As I mentioned, it really is not a great fit for everybody, but people are often surprised at what they need going in, what would make them a good fit or would not. So I'll talk about personality, what it helps to have, what you don't really need or what people tend to overvalue, and how you might further test this (in case a 30-minute presentation can't convince you one way or the other to radically change your career).

Okay, so first up, personality. This is an example of a fantastic charity entrepreneur. I'm not talking about Prince William; I don't really have an opinion on whether he can make a good charity entrepreneur or not. I haven't spoken to him personally. But I have spoken to Rob Mather. He really embodies what a fantastic charity entrepreneur might look like. One of the things I want to highlight about him is his personality. Personality is so key, when it comes to charity entrepreneurship. It's one of the first things we look for in our vetting process, and one of the things that I think determines eventually whether your charity ends up being massively high impact or not.

You need a lot of different things. You need to be resilient. There are going to be bad days, bad weeks, and potentially even bad months where you think your charity is low impact, that it wasn't worth founding, and that it's too hard to get yourself motivated. And as the founder, you have to motivate not only yourself, but also your co-founder and your employees. You have to be ready to take those shocks and keep moving on, keep moving through them even when it's tough.

The next thing is being ambitiously altruistic. So a lot of entrepreneurs love ambition. It's a very common thing, but it's really easy to be ambitious about the wrong thing. If you're ambitious about how big your charity is, your charity might get really big, but it won't necessarily do any good. What you need to be ambitious about is how many lives you save, or whatever your end line metric is for doing good. That's the thing you have to be laser focused and truly ambitious about.

The next thing is results oriented. Quantified measurement is one of the things that makes EA different from many other movements. We really want to see concrete, specific results, and have data to back it up. Staying focused on this will stop your charity from diverging into 100 other projects that might not be as high impact, and it really can make a difference in the long term.

The next thing is being open-minded. You won't have all the skills you need. Nobody does, when they first found a charity. You have to be able to update based on the world changing, based on testing out one thing and it not working, based on advice from people in the field, people who have worked in specific areas that you don't have knowledge in. You have to be ready to amalgamate all these different views, and come up with a coherent answer, and update as new data comes in.

Similarly, it's important not to be afraid to make mistakes. You will make mistakes. Every charity entrepreneur does, and will. Being able to admit these mistakes transparently, learn from these mistakes, and update them can be the difference between your charity eventually succeeding, and you continuing to make the same mistakes again and again.

Next, self-motivated. This might be the most important criterion. You really have no boss, no person whipping you at the end of the day to get the work done. You have to really care about your charity and be able to put in the hours, to be able to work yourself through the project. One of the easiest kind of litmus tests I have for charity entrepreneurship fit is, can you get yourself through a self-directed project? Can you complete an online course without anyone needing you to? Can you start something where only you're responsible if it succeeds or fails? That sort of thing is really challenging for a lot of people, and it's really, really challenging to do a charity like this. You will have your co-founder, you will have your mentors, you will even have funders you have to report to, but not at the same level of regularity that any other job will make you. You have to be self-motivated.

Creativity also helps. There will be a blank slate. You won't necessarily know what the next steps are, and you have to come up with ideas. How to test one thing, how to test another thing. If you come up with five ideas, five ways to test a given concept, that's the limit of how good you can get: the best of five. If you come up with 30 ideas, you can test them all, you can evaluate them all, and come to the best of 30. That makes a huge difference for your charity's impact.

Next, doing it for the right reasons. This is a bit different than being ambitiously altruistic. You really, really have to be focused on doing good for the world. If your goals are different, if your goals are divergent and you want to create a charity to look good, or to impress a partner, or something like that, your charity won't end up being high impact. You really have to be laser focused on that, doing it for the right reasons, with an altruistic mentality.

There are some other things it helps to have. It's nice to be highly competent, whatever that means. Kind of general ability, conscientiousness, IQ, that sort of thing. The EA community is a huge asset, a bunch of skillsets that you can tap to, a bunch of people who really want to help you start a charity. Social skills or research skills, it's really great to have one of those. Your co-founder can balance you out and have the other one. And experience working in a small organization charity can give you a sense of what it looks like from the inside. You tend to think that every organization is perfect, and when you get on the inside, you tend to see how held together with glue and tape it really is.

What's less important than people generally think? Well, one is a degree. A lot of people think that if they want to start a global health charity that's fantastic, they need to get a global health PhD. Unfortunately, those programs end up being too unspecific a lot of the time. For my charity, SMS Vaccine Reminders, you might have only read a page or paragraph in a global health program about this sort of intervention. It's just very, very specific, not to mention the country context. What you need to be able to do is become an expert, it's not necessarily through a degree; it's through reading the studies, reading the research, getting very, very expertised in the very narrow domain that you want to start a charity in. You want to be able to talk to experts and engage with them at the highest possible level, but you won't get there from doing a PhD program. You'll have to do the independent learning on top of that, in either case.

Also, targeted experience. At a health nonprofit, you might be able to pick up some good habits, but often your role will be very specific. If you're working for a large, even a well run health organization, often you'll be running one very small component of it, whether that's a comms job or a research role. That will give you some skills in that area, but as a charity entrepreneur, you really will need to learn a little bit of how to do everything. Some people might come into charity entrepreneurship with five out of 100 skills that they need, and other people might come in with nine out of 100 skills that they need. Either way, you still need to be able to develop 91 skills. A lot of it comes down to being able to learn things on the fly, try things out, pivot and update based off evidence, talk to mentors and utilize their skills. That sort of thing is going to be far more important than coming in with a few extra skills.

Next thing is, connections in the field. Connections in the field are super important, and you do need them to have a successful charity. But you'd be amazed how willing these people are to talk to you. If you come in informed and keen, and with some expertise or some funding, a lot of these organizations are extremely excited to talk to a young or experienced person who's getting involved. They want to see other charities. They care about this stuff a lot. And they're not getting a thousand emails a day, if they're running some small program out of India.

In general, it's a very, very easy to build the network, and that is how you build the network, by working in the field. It's helpful to reach out these people and have a quick Skype with them, tell them what you're doing, tell them what you're considering, ask them for advice. Everyone's been very happy to help when we've done this on multiple different projects, across multiple different cause areas. The one exception to this is government connections. It's hard to build government connections; they're not willing to talk to you. If you're doing a job where you need government connections, hire someone who has the government connections. That's the advice there.

So, a little bit about further testing. The best way to test if you're a great fit for charity entrepreneurship in the way I'm talking about it, might be applying for our incubation program. I'll talk a little bit more about what that offers and why you might consider it, but we do have a process that we've used before, on entrepreneurs, that has been fairly successful at selecting the kind of people who might start a GiveWell incubated charity.

We have a quiz on our website. It's a lot less intensive than doing the full incubation program process. It's pretty quick, about three minutes, and it will give you a sense from a personal perspective if you might be a decent fit or not for charity entrepreneurship.

Finally, generally on our website we're trying to put out as much information as possible. So people can self-select, people can consider whether they're going to be a good fit for charity entrepreneurship or not. Our mail list, we send out of all of our relevant research as well as like, helpful things like Facebook group links, to ways that you can ask people questions, and all that sort of thing. So that also can help to give you a sense slowly of whether this might be a good fit as a career path or a bad fit.

In general, though, don't be too discouraged. A lot of the strongest charity entrepreneurs I've talked to are scared, they're nervous, they're not the archetype of a gung ho, confident entrepreneur. Some of them are cautious. Some of them are detail-oriented, some of them are not gregarious. Don't let superficial entrepreneurship associated traits fool you. Instead, try to get as good as sense as you can from external people who have looked at it before, or by talking about it, or by reading the content from people who have started successful charities.

I want to talk a little bit about how Charity Entrepreneurship as an organization is aiming to help charity founders. The first thing is, coming up with a really fantastic idea to run a charity on is hard, especially if you're trying to become a top GiveWell charity or top Animal Charity Evaluators charity. That's not an easy bar to beat. Thankfully, we've been able to do a lot of research to narrow down the space a little bit into some ideas that are extremely promising. This is a spreadsheet we did on different global health ideas, narrowing down to what ideas might feasibly be competitive with the top GiveWell charities. They might be evidence based, and they might be cost effective enough to do a really good thing.

Here are a few of them in particular. Tobacco taxation looks fantastically cost effective if you can get the right country. Conditional cash transfers have a case for very strong impact, and are being done almost nowhere by NGOs. This year, we're going to be focusing on animal interventions, and researching that, and looking for the highest possible impact interventions that one could start in the field. We're doing research a bit different than say, GiveWell, or Animal Charity Evaluators. We're looking for gaps, areas that could be really promising, could be really effective, but don't have anyone working in them necessarily.

Malaria is a fantastic place to work, but AMF is doing a really good job, I wouldn't want someone to start another bed net charity. But there are areas that are both fantastically high impact and neglected, as in no one's working in the kind of way that we as effective altruists, or we as people who want help the world, would like to see it done.

So the incubation program that we're running is taking place from June 15th to August 15th, and we'll be hoping to run it every year. We really want to make the process of founding a charity as easy as possible. So we're giving structured support that slowly withdraws, until people are fully independent and standing on their own two feet. The first month will be something akin to a university class. There'll be activities, there'll be pairing with different co-founders to test out your abilities in different ways, there'll be explicit teaching about cost effectiveness, or fundraising plans, all the hard skills that you might need to run a really good charity.

The second month, you'll be paired with co-founders on an idea and start working on a project, but with a lot of support from teams of people who have already successfully founded charities. Finally, over the next six months, you'll be given a seed grant, to financially support yourself so that you can really become a true domain expert before seeking external funding. Seed grants are about $50,000, depending on how many charities apply.

This structure allows someone who maybe doesn't have a ton of experience in working for NGOs, or nonprofits, but is able to build the experience as they go and get really competent and capable, to start a high impact charity.

We really don't want it to just end after the seed grant ends, we want to continue to support charities as long as they need it. We're trying to build a community such that people can continue to stay connected, whether that's over Skype or Facebook, or a co-working office that we're going to have. We want to have joint office space so that people can feel like they're working with a team instead of working alone or with their co-founder. The seed grants I already mentioned. We'll also connect people with long-term funders. We don't want to see these charities just run for six months, and then flounder. Most of the connections will be people who are very keen on founding new charities, and ongoing mentorship.

So I still continue to Skype with the projects that we've helped, and help them with the most difficult issues, so they can have an external set of eyes for as long as they need it.

This is a quote from Fortify Health, and I think it's a really important one, because it shows that not everyone knows that they're going to be a perfect fit for this. Some people think it might be too hard or impossible, but a lot of people can do it. You can rely on the process to figure out if you're a fantastic fit.

Just to reiterate on the goal, there are fantastic charities in the world, but there aren't not enough of them. We need more really, really good charities, more Humane Leagues, more Against Malaria Foundations. Charities that make a massive difference at cost effectiveness far greater than a standard charity. There's still gaps, and room to do it. The main thing missing is entrepreneurs, people who will be able to step forward and take on this risk, and potentially start incredibly successful charities.

Questions

Question: Earlier, one of our speakers, Dr. Glennerster, said that she really advises young people to make sure that they spend some time in an effective organization so they know what an effective organization looks like. What do you think about that?

Joey: Yeah, it helps a lot. When people ask me what they should do if they're still working on their degree or are looking for internships, I always say, prioritize how good the organization is. It doesn't have to necessarily be in a tightly related area, but if you work for a charity like AMF, or pick up some of their management practices, that's going to be one of the best things you can do to set yourself up to run a charity really well.

Question: It seems like the charity space has a proliferation problem, where there are lots of small charities, often nipping at different corners of the same bigger problems. What's your take on that, and how do you think about people joining versus starting charities given that reality?

Joey: So, we're pretty pro starting versus joining. Joining organizations, whether they're small or big, it's incredibly hard to change them in an effective direction. You can ask a lot of people who have worked with these organizations to get a sense of that. There are lots of charities, but most of them are incredibly small. You'll see a statistic like there's a million charities, but almost all of them have an operating budget of under $50,000 or something like that. So it's not like they're taking out huge chunks of global problems. What you really have to look at is the scale of the remaining problem, and whether you can start a charity that starts to cover some of that problem.