Articles

Ending Factory Farming

Ending Factory Farming

While there are causes for optimism, factory farming is still on the rise globally, and we have to understand it to eliminate its harms. In this broad-ranging talk from Effective Altruism Global 2018: San Francisco, Lewis Bollard talks about the situations for various sorts of animal, the efforts to help them, and how different strategies may be helpful in different national contexts. A transcript of Lewis's talk is below, followed by questions from the audience, which we have lightly edited for readability.

The Talk

As effective altruists who care about the wellbeing of individuals, it's natural for us to want to end factory farming, which may be the greatest source of suffering on earth. I think it's also natural for us as optimists and people who believe in technology to think that perhaps the end of factory farming is imminent or even inevitable.

You may have seen headlines recently that clean meat is just around the corner. That US meat consumption is falling, and that that the end of meat is nigh in the world. And while there have certainly been a lot of exciting developments recently, these are all headlines from six to seven years ago. The unfortunate reality that we have to confront is that factory farming is not inevitably going to come to an end. The reality is that right now, factory farming is continuing to grow.

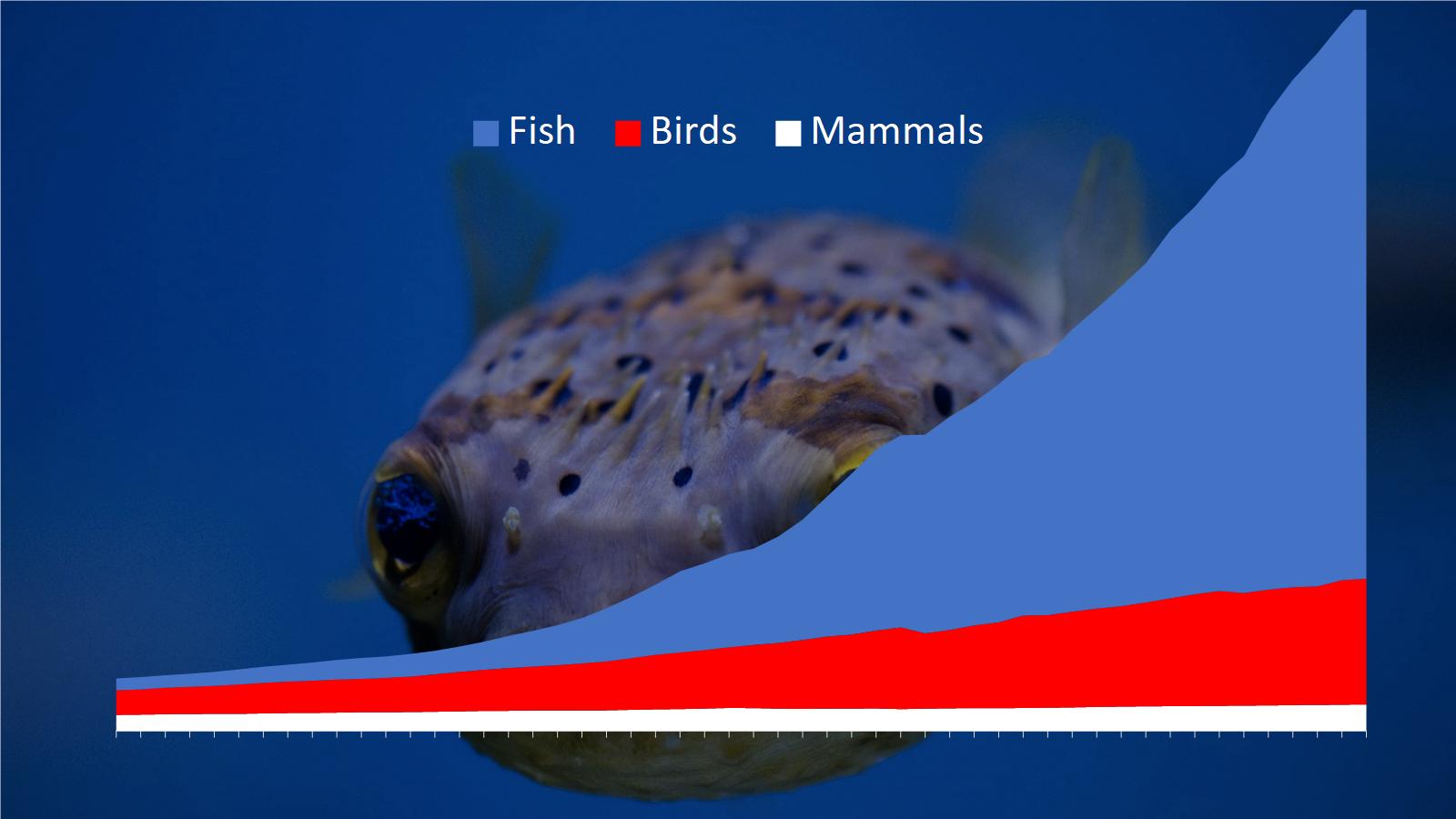

This is a graph that shows the number of vertebrate farm animals, including fish, on farms globally, and as you can see, there are more farm animals today in factory farms than ever before in history, and it's continuing to grow at the same rate as it has been for the last 20 years. So what can we do about this? Obviously we need to take a number of approaches to this problem, including ones focused on technology, but I want to focus today on three things that I think have been driving the increase in the number of animals in factory farms, and that I think offer particularly important, tractable and neglected approaches to reducing farm animal suffering.

The Plight of Birds

The first is the plight of birds, and specifically chickens. So what you see in this graph is that over the last 50 years, the number of mammals alive on factory farms globally has barely increased, while the number of chickens alive at any point in time has significantly increased, up to a point of 23 billion alive at any point in time. That equates to over 60 billion slaughtered annually, because most of these chickens are broiler chickens who live short lives. And so when we think about what we can do to improve the plight of birds and particularly chickens, it comes down to two types of these birds. The first, you're probably familiar with, is the plight of layer hens.

The first is the plight of birds, and specifically chickens. So what you see in this graph is that over the last 50 years, the number of mammals alive on factory farms globally has barely increased, while the number of chickens alive at any point in time has significantly increased, up to a point of 23 billion alive at any point in time. That equates to over 60 billion slaughtered annually, because most of these chickens are broiler chickens who live short lives. And so when we think about what we can do to improve the plight of birds and particularly chickens, it comes down to two types of these birds. The first, you're probably familiar with, is the plight of layer hens.

This is a photo I took in India last year at a battery cage facility. It's hard to imagine a more intense form chronic suffering that you can inflict on an animal. We know from preference studies that these birds, given a chance to get to a nesting box, will push through a cage door as hard as they will to get to food after 24 hours of deprivation. So the mere fact that they're not getting access to a nesting box here - and we know there are similar desires to get to perches, to get to dust bathing ability - shows you the degree of behavioral deprivation inflicted on these animals, typically for more than a year at a time.

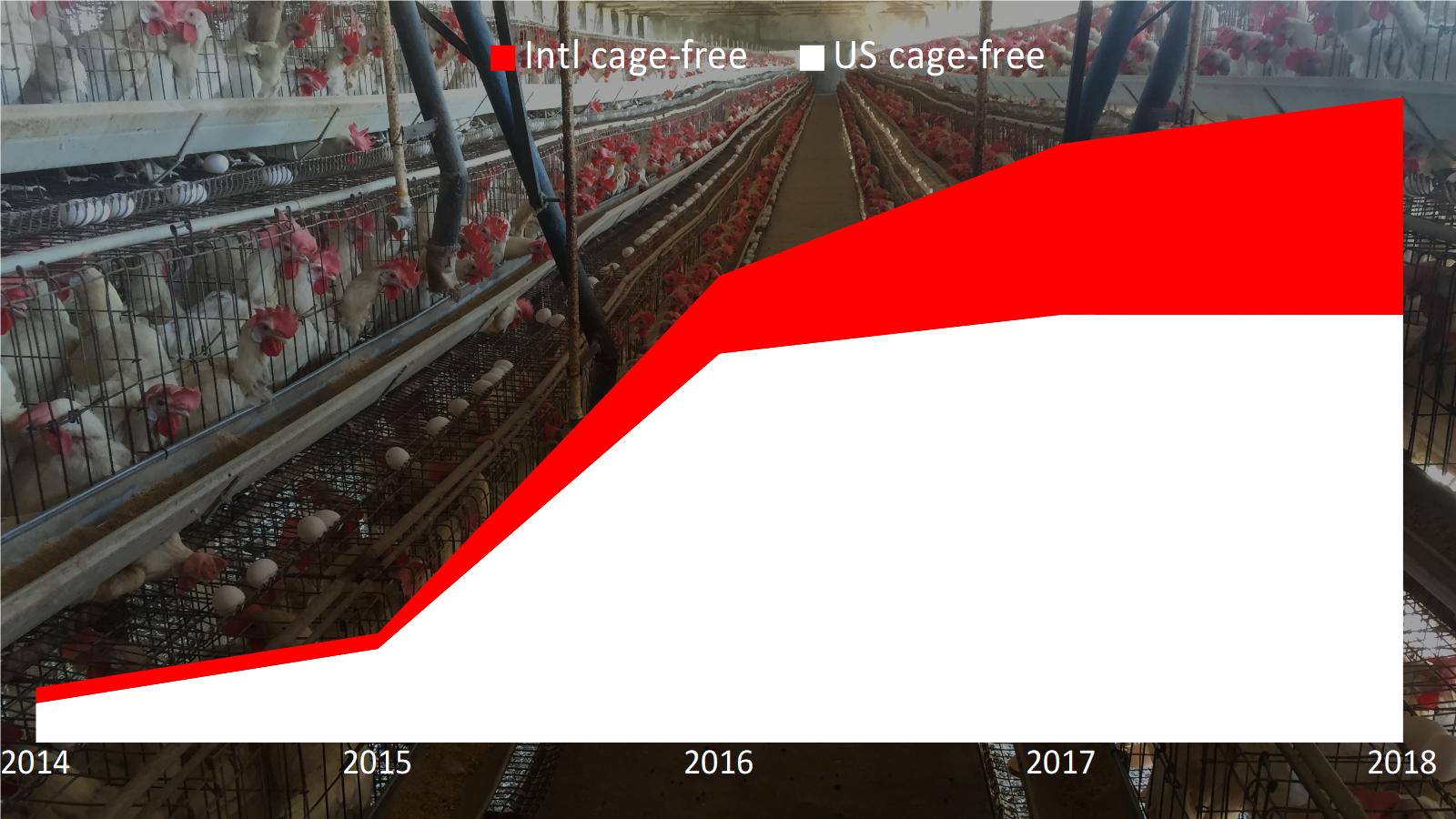

The good news is that there has been progress. The first progress that we've started to see has been over the last four years, initially in the US, going to corporations and securing pledges to get rid of battery cages. Now up to a point, those pledges, if implemented, will benefit about 275 million hens a year. Those campaigns have now gone international, working in Europe, in Latin America, increasingly in Asia, and have reached a point that those international pledges are set to benefit about 130 million hens a year if implemented. But of course that raises the question of if they will be implemented.

Here's the evidence that we have today; these are the latest figures. As of last month, there were 55 million cage free hens in the US. Now that's a significant increase from a few years ago when there were fewer than 20 million cage free hens in the US, but obviously there's still a lot of work to be done, and so one of the priorities for the movement within affecting layer hens is getting the implementation of these pledges that have already been secured.

The other priority is reaching the other group of chickens, the broiler chickens. So as most of you probably know, broiler chickens are a different strain of chicken that are raised separately from laying hens, and are raised for meat. And as you'll see in this photo that I took of a broiler chicken in India, their problem is less that they're in cages - they're normally not in cages - and more the way that they've been bred in the first place, that they have been bred to suffer. There have been studies done on broiler chickens with leg problems, which is a common ailment amongst chickens, in which they've been offered feed laced with pain relief or feed laced without pain relief, and chickens who don't have these leg problems, who don't have these genetics, show no preference between the two. But the chickens who do have these leg problems, the chickens like this one here, that have been bred to grow too large, too fast, choose the pain relief laced feed, suggesting to us that these birds are in chronic pain. And when we're talking about 16 billion alive at any point in time, about 60 billion a year, given the short lifespan, that's a huge amount of potential suffering.

So what can we do to alleviate it? Obviously one thing is to reduce the amount of chicken that people eat. And I'll talk a little bit about some of the efforts in China on that later on. The other thing we can do is to reduce the suffering of each chicken, and so advocates have been working in the US over the last two years to secure five asks of companies.

The first is to change the breed, to move away from these breeds of birds that are in constant pain. The second is to reduce the overcrowding in chicken barns. The third is to improve living conditions, in particular litter, lighting and enrichment. The fourth is to move to a less cruel method of slaughter. And the fifth to ensure the auditing of those pledges. There's already been significant progress to date: Burger King, Subway, major food service companies in the US have committed to these pledges.

And advocates are right now engaged in the toughest fight of all: the fight to get McDonald's to give up this incredibly cruel system of raising chickens. McDonald's accounts for about three to four percent of the chicken purchased in the US every year. So the decisions they make will have a huge impact directly on chickens, about 270 million chickens a year in their supply chain. But they will also have huge knock-on effects, so it's critical that advocates win this campaign to ensure better conditions for chickens in the US, and I think likely, too, in the future around the world.

The Plight of Fish

This brings us to the second issue, the only group of animals, or vertebrate animals, that's larger than chickens on farms. And that's farmed fish. So this graph shows the increase in the number of farmed fish, individual farmed fish, over time globally. The best estimate now is that at any point in time, there's between 75 billion and 140 billion farmed fish, confined in fish farms globally. The estimate is that there may be another 1 to 2 trillion wild caught fish who are slaughtered globally. Most of them are very small fish.

This brings us to the second issue, the only group of animals, or vertebrate animals, that's larger than chickens on farms. And that's farmed fish. So this graph shows the increase in the number of farmed fish, individual farmed fish, over time globally. The best estimate now is that at any point in time, there's between 75 billion and 140 billion farmed fish, confined in fish farms globally. The estimate is that there may be another 1 to 2 trillion wild caught fish who are slaughtered globally. Most of them are very small fish.

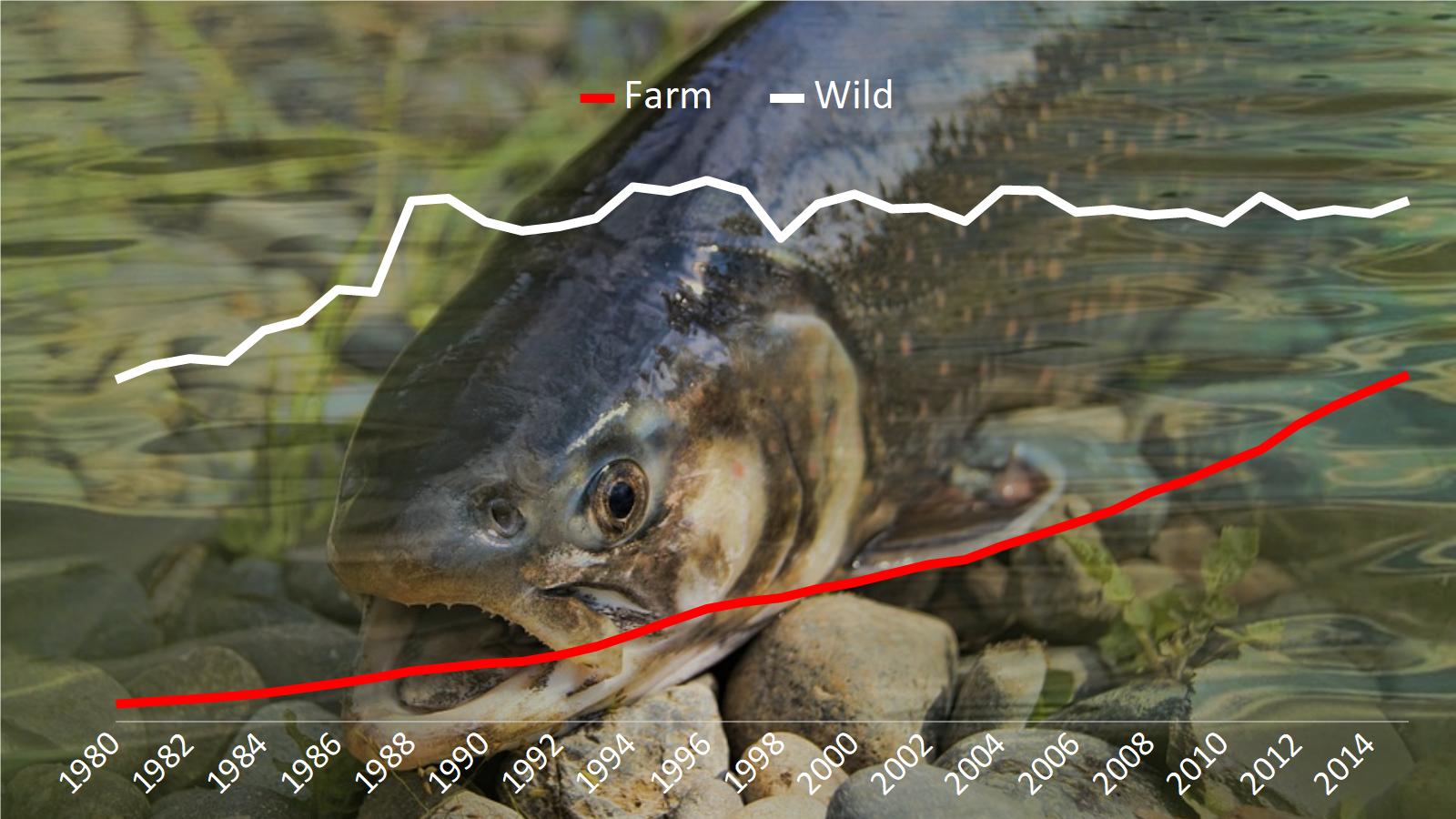

This graph doesn't quite represent that. This graph shows more the trend line. This is in terms of tonnage rather than in terms of individuals because we don't have good individual data for wild caught fish. But what you can see is the trend over time is one in which wild caught fish is not increasing, while farmed fish is increasing rapidly. So something that's appealing about focusing on farmed fish is not just that they're more directly under our control, and that there's a greater lifespan of chronic suffering to affect, but also the fact that this is a trend line hitting in a very bad direction. So I want to tell you just a little bit about visiting a fish farm in India last year. And to me what was surprising about it was that from a distance, a fish farm really didn't look that bad.

So, all the commercial facilities we visited were like this. Huge ponds the size of multiple football fields. You don't obviously see overcrowding, you don't obviously see incredibly dirty water. We know very little about what these fish are experiencing beneath the surface, but you don't immediately see the problems. But I think somewhere where you do immediately see the problems is when you look at the slaughter of these fish.

This is the photo that I took at a fish farm last year, and the method of killing fish, both farmed fish and wild caught fish globally, is truly barbaric. So these fish were hauled out of the water. Many of them were crushed to death underneath each other. Some of the other ones were live disemboweled, and the ones that weren't suffocated over the course of several hours. So we followed some of these fish to a live market, where they were still alive hours after they had been caught.

And I think the thing which is most striking with this particular welfare issue is how simply it could be solved. So, technology already exists to stun fish. Electrical stunning technology is relatively cheap. Some European companies like Tesco already require this throughout their supply chain and yet we see that over 90 percent of the fish globally are not stunned prior to slaughter. So in addition, of course, to wanting to reduce the number of fish, there are some really simple things that with a bit of pressure, could reduce a huge amount of chronic suffering, over 100 billion farmed fish a year, potentially over a trillion wild caught fish a year, if we could get stunning technology in place.

The other positive trend on fish recently is the attention that the issue has gotten from the media. So just in the last year, we've seen headlines from the Washington Post in terms of looking at the scientific consensus that fish feel pain, from the Smithsonian magazine, again, talking about fish pain, from the New York Times, talking about fish depression and increasing evidence that fish can feel depression just like we can, and just like we know that mammals and likely birds can too. From NPR, talking about the way that wild caught fish are being treated. And finally from USA Today, talking about progress in Switzerland and potential progress in the UK toward banning the boiling alive of lobsters and crabs.

Farm Animals in China

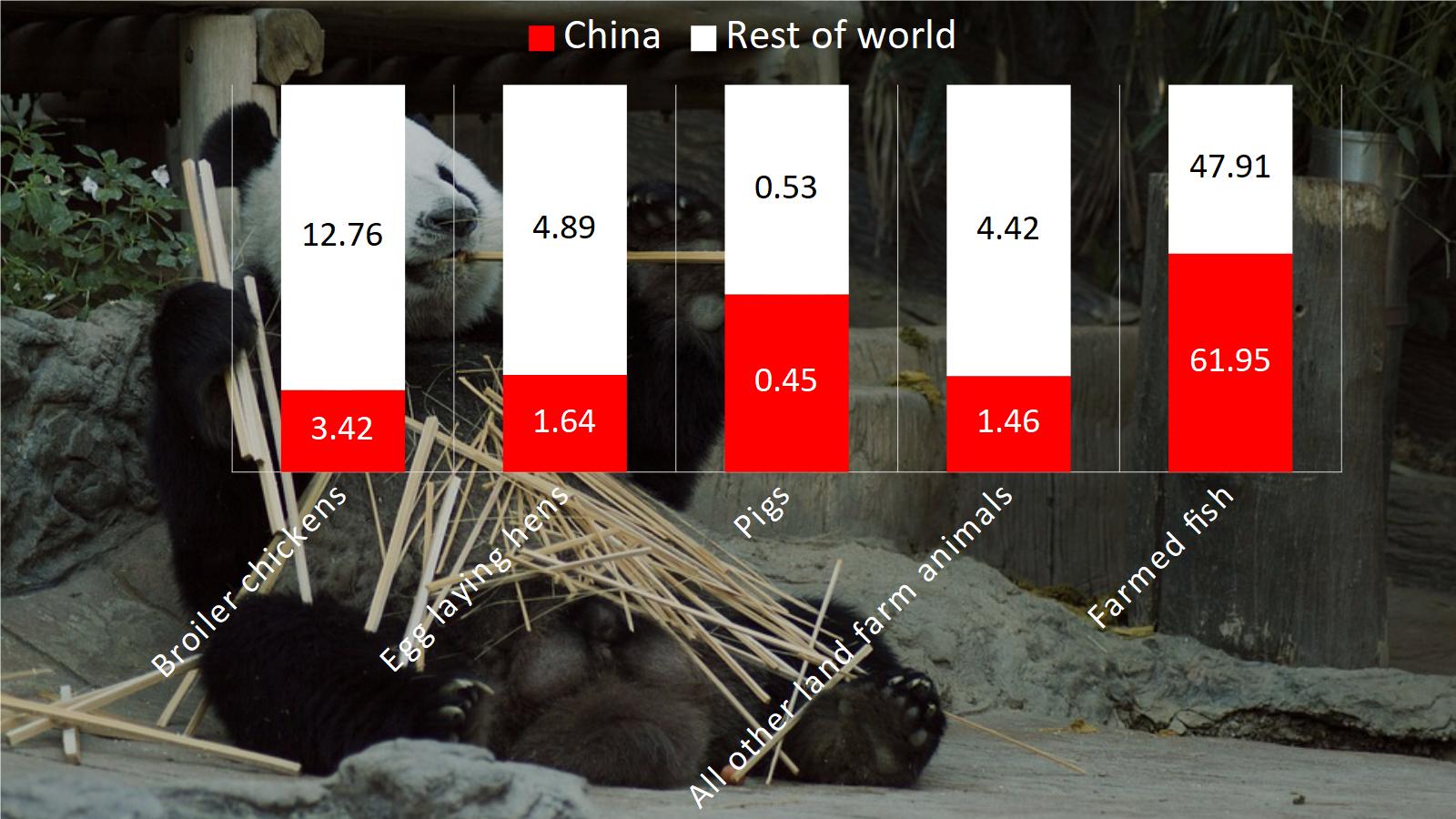

The third major driver of the increase in the number of farm animals globally is China. So as China has gotten richer over the last 20 or 30 years, we've seen a dramatic increase in the number of farmed animals in China.

This graph shows you the portion of the world's farm animals of each variety that are housed in China currently. And what you see is for chickens, it's about a fifth to a quarter. For pigs it's about half the world's farm animals, for farmed fish, it's over half. And this is not a case of China exporting to the world for the most part, though there's a little bit of that. This is primarily for domestic consumption, and so if you care about the plight of animals on farms, you have to care about China and the trajectory of this issue in China. And I think there are a number of hopeful signs on that.

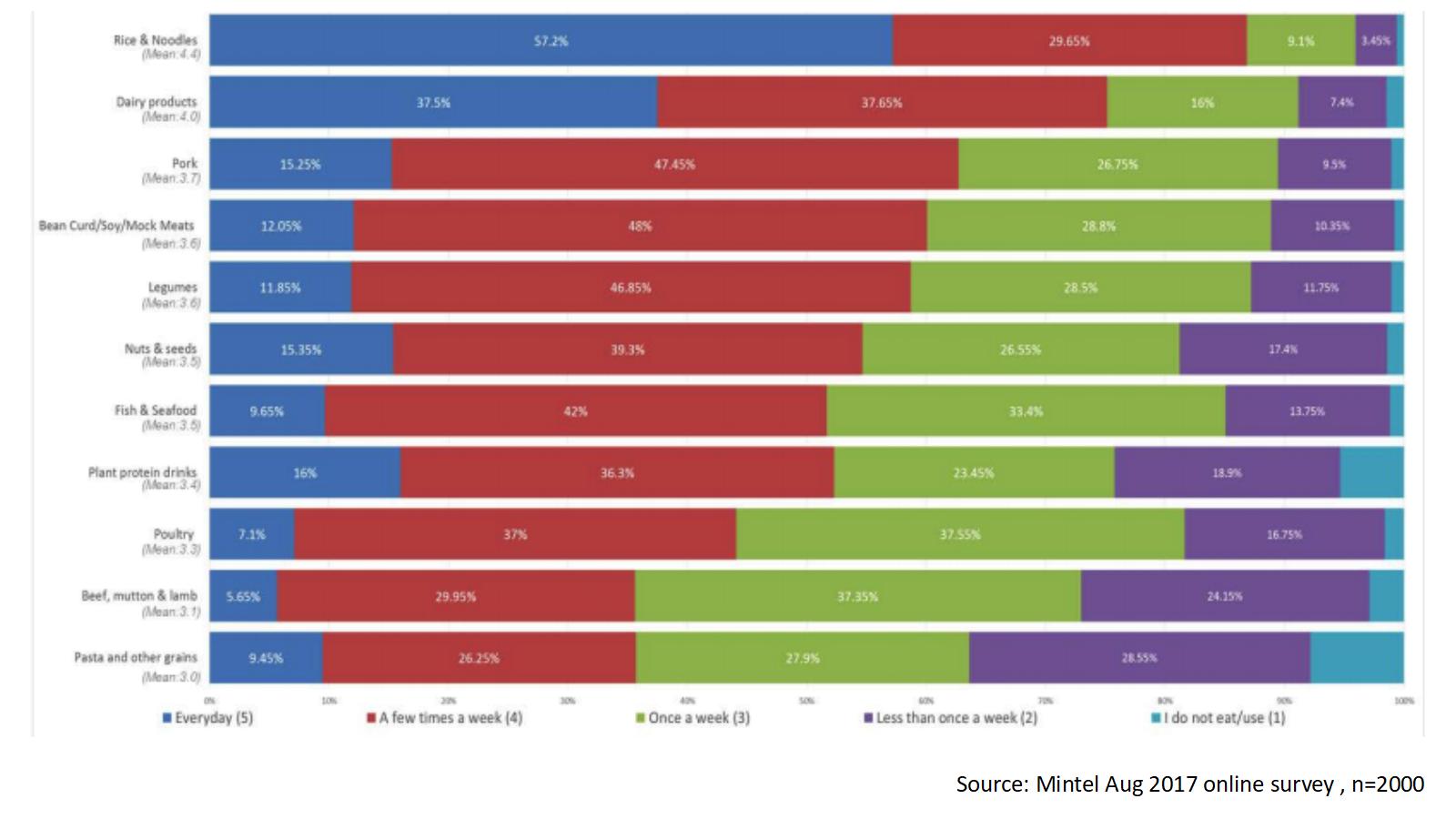

It may be a little hard to read what this says, but this was a survey done at the end of last year, of 2,000 Chinese consumers. They were asked how often they eat each of these groups. So in blue means they eat this group of food every day and red means a few times a week, green once a week, purple less than once a week and the light blue means they never eat this food. And what you see is, despite some of the headlines you may have seen, there's very little vegetarianism or veganism in China. There were very few people, less than one percent, who said that they never ate pork or never ate other animal products. However, what you also see alongside this, is that the majority of Chinese consumers in this survey said that they don't eat meat every day. In fact, not only do they not eat pork, they don't eat chicken or other types of meat every day, and it's far more common to eat it on a weekly basis.

And you also see that Chinese consumers eat plant protein on a daily basis. So things like mock meats, things like legumes, things like nuts often mixed together with meat dishes. So for instance, a tofu and pork dish is regularly part of the diet. And I think this provides a basis to work from that we don't have in the US, because these alternatives are already readily available, and they're already accepted as part of the Chinese diet.

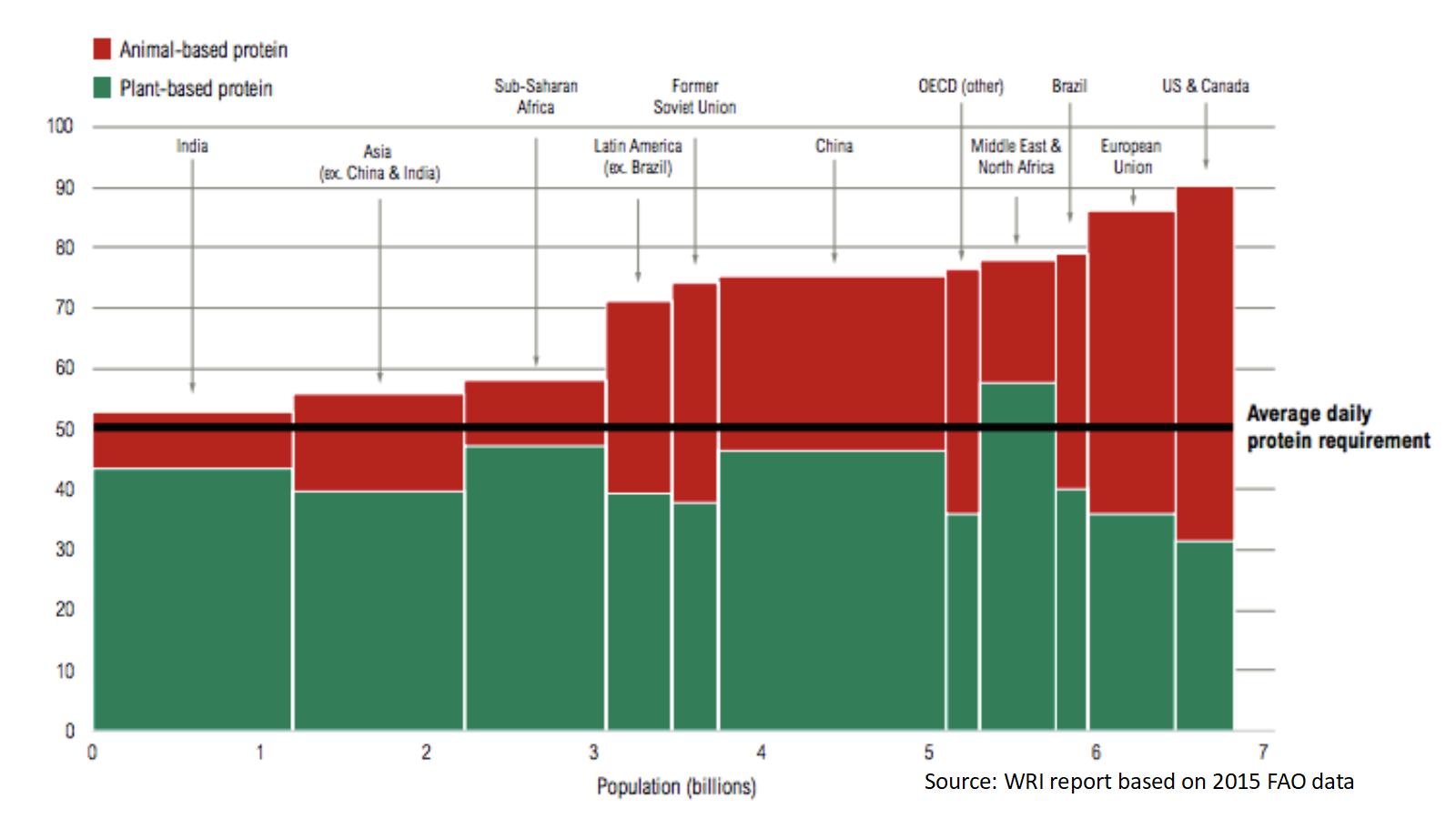

Here's a graph that shows similar data in another format. So what you see here is in green, plant protein, and in red, animal protein. You can see in the US, we're incredibly dependent on animal protein. About two thirds of our daily protein average intake is coming from animal-based protein. When you look at the rest of the world, that's just far less the case. So the average Chinese person and the average Indian is getting more plant-based protein now than the average American. And what you see particularly when you look at somewhere like India, like the rest of Asia and China, is that the animal protein segment is not as big as it's gotten in the US. It seems like there's the potential to shrink that without people going below the level of daily protein required. So although we obviously want to increase the percentage of plant protein, there's also the potential to simply reduce the percent of animal protein.

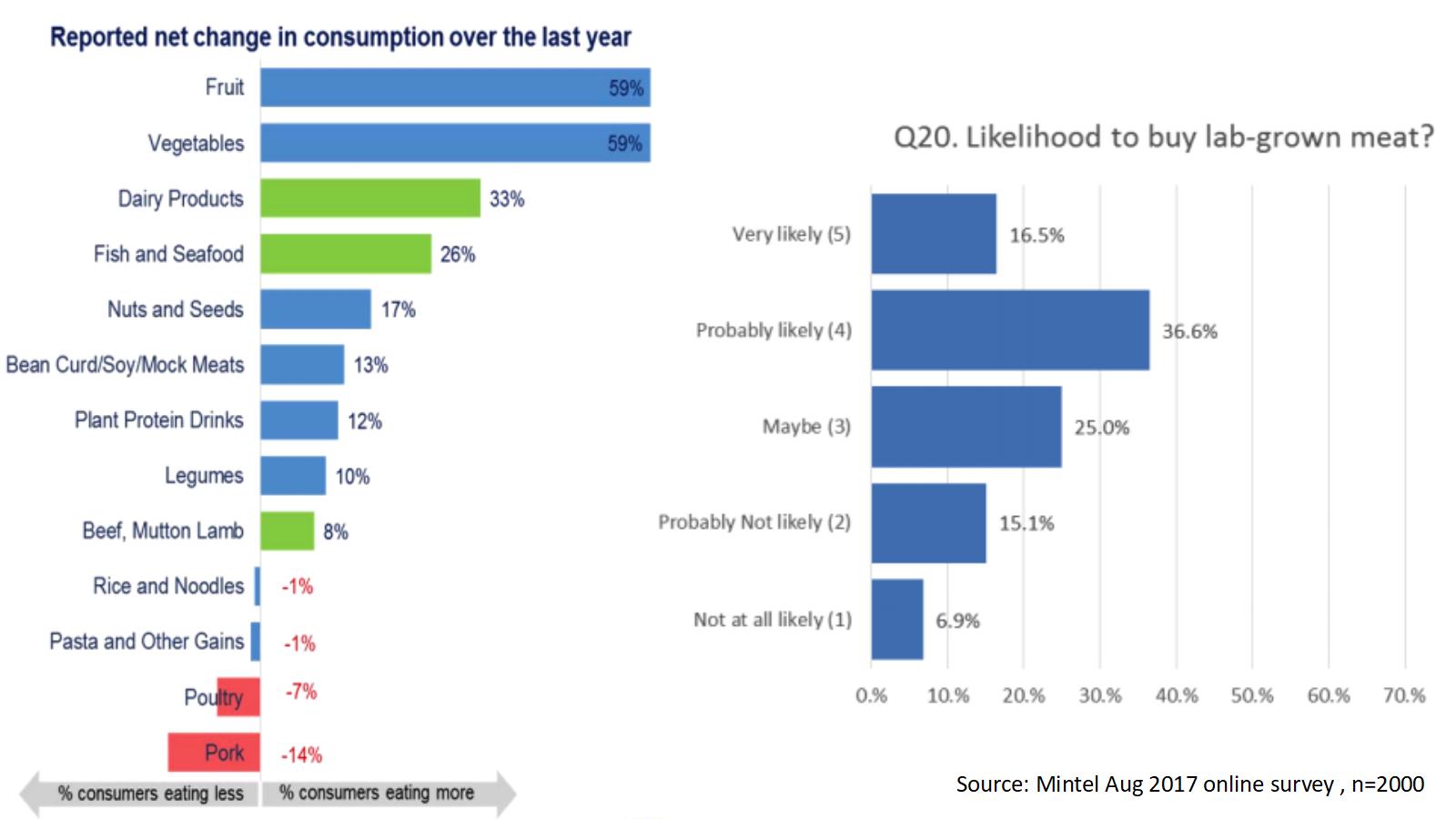

And here's two more causes for optimism. So what you see on the first side was, again the same survey, reported changes in consumption, so people everywhere always say they're eating more fruits and vegetables and you can take that with a grain of salt. But the thing that I think is interesting here is that poultry and pork consumption are reported to be down. We're actually seeing that showing up in the national statistics. Now at the same time, fish and seafood consumption is up. So it's not clear that this is totally worked out net positive, but I think there's a positive trend there. I think there's also a positive trend in the increase in plant protein consumption, which sort of goes against the narrative that China is moving away from plant protein and toward animal protein. The other thing you see is a receptiveness to clean meat, which seems to be greater than the receptiveness that we've seen to clean meat - meat grown from cells - in the US. And so if you think that that's likely to be in the future, down the line, it suggests China may be a good market for that.

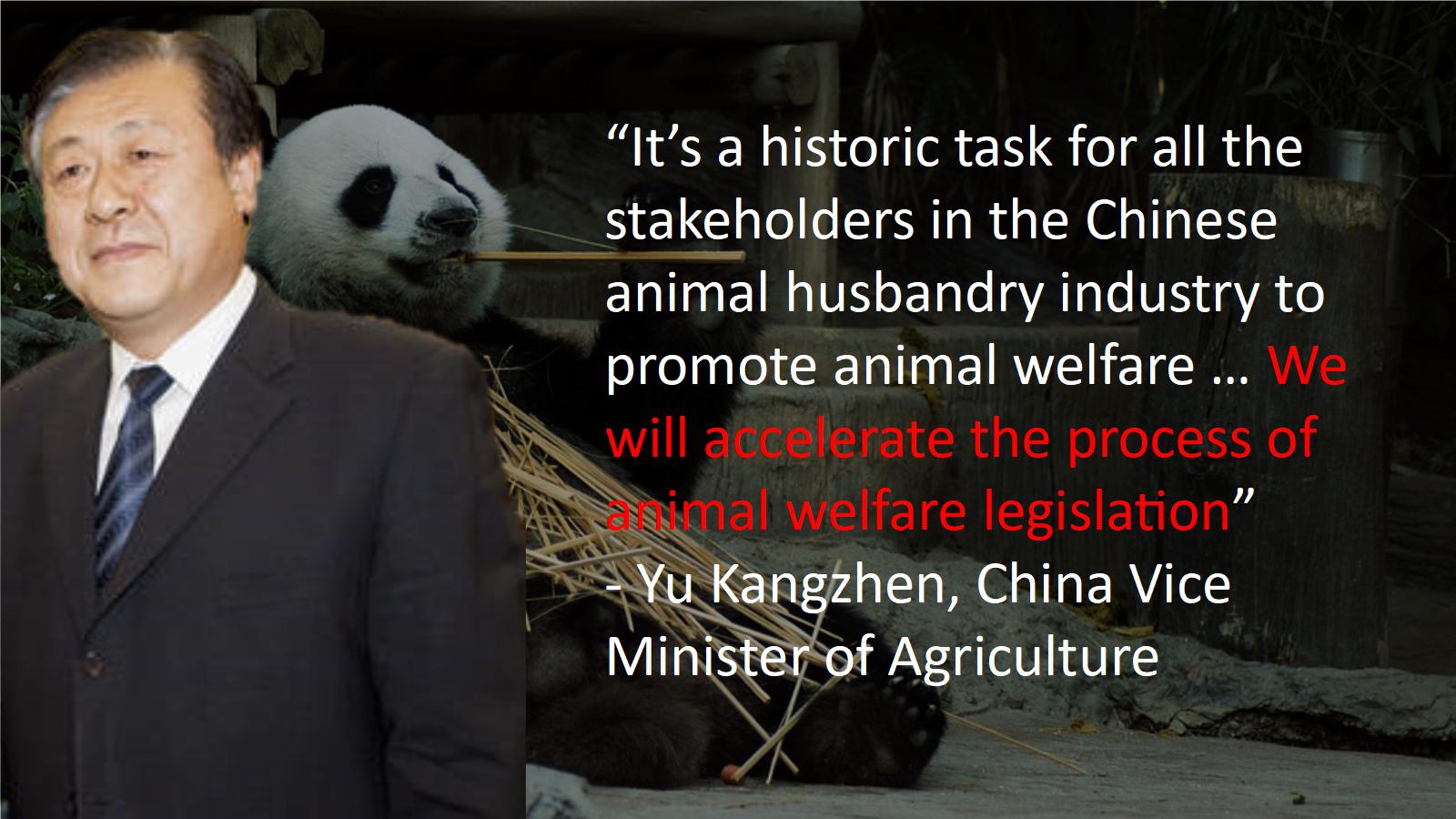

The one other cause for optimism that I want to highlight is the change within the Chinese government. So something you've seen on a number of social issues in China, for instance, on environmentalism, is that the Chinese government was traditionally silent on the matter, but that once Chinese government officials started talking about it, they legitimized the issue and were able to achieve policy changes far faster than we've achieved them in the US. And my hope is that this is the start of a trend like that.

So what we saw last year was what is to my knowledge, the first time Chinese government official has spoken in favor of animal welfare, and indeed the first time that a Chinese government official has called for animal welfare legislation, which China doesn't yet have. And in fact also in the same speech, called for a set of regulations and technical standards. And so my hope is we'll start to see the dividends of that.

Questions

Question: Meat consumption is on the rise. As the world gets wealthier, we see this, especially as GDP increases in the developing world. How can we go about thinking about preventing norms from being established before meat consumption becomes normalized?

Lewis: Yeah, this is really interesting. So, there are certainly efforts underway in parts of the world, for instance, in developing parts of Asia, to encourage vegetarianism. But I think that it's often hard in a developing nation context to tell people that they shouldn't be able to eat something. And so although I think people often look at this as the low hanging fruit to stop people from eating meat before they start eating it, I tend to be a little more skeptical of that. I tend to think that it's, it's perhaps going to be easier to get people in a place where they already have all the necessities of life, and they can start to think more about these concerns. So I mean, one cause for optimism is that you hear a constant narrative about India eating more meat. The statistics don't really back that up. So, the percentage of Indians who are vegetarian is the same as it was 10 years ago. The amount of red meat being consumed in India is down from 10 years ago. The amount of poultry being consumed is only slightly up. The amount of fish and seafood is only slightly up. So I think this narrative can be overblown a bit, but I also think that, well, there's certainly some hope along those lines. I think we have to be delicate because of the situation.

Question: You mentioned that it seems like a really good sign that there's a Chinese official backing animal welfare legislation, but to someone who lives in the US, making progress here may seem pretty impervious. Is there something that they could do, particularly in the China animal welfare context?

Lewis: Yeah, well, I think for people who are themselves Chinese or Chinese American, I think there is more you can do, so I would certainly encourage anyone who fits in that category and is interested in animal welfare to come speak to me or to Brian Tse, who's also at this conference, and perhaps maybe here in the audience. I think that if you're not Chinese, it's likely that there are things you can do for international organizations. Now, whether that's your comparative advantage, I don't know. I think it probably depends a bit, but there are international groups that are working at the invitation of the Chinese government. So on the animal welfare side, groups like Compassion World Farming, World Animal Protection, and on the meat reduction side groups like Wild Aid and GOBlue.

Question: At the beginning of the talk, you mentioned specific campaigns like the campaign for McDonald's that seems to be pushing the frontier in the right direction, but are there campaigns that you would like to see and would throw funding behind if only they existed? And if so, what are these?

Lewis: Yeah, so there are certainly a lot of campaigns that we'd love to see in the long term. I think that in the short term there's really a lot of value to focus. And so although for instance, I'd love to see campaigns focused on fish, I'd love to see campaigns pushing for things beyond immediate cage free on hens, campaigns focused on other species, I think there's been a lot of value to focusing on one issue at a time. And so I wouldn't encourage US advocates to take on other issues right now necessarily. And I think internationally it really depends on where things are at. I think in Europe because things are furthest along, there's the most scope to advance sort of new issues like fish, like perhaps mutilations of pigs, and other of the new welfare issues. Yeah.

Question: For lots of cause areas that EAs focus on, they are really looking for an evidence basis, and it seems pretty hard to get this when you're working with an n of five, a really small number of policy advocacy campaigns. What makes you think that a campaign may be something that's worth putting money and support behind?

Lewis: Sure. Well, I think what the corporate campaigns, we have much more than an n of five. I mean we have an n of 530 in terms of corporate victories. So, and you know, obviously more in terms of corporate... not victories yet. So I think on policy it's certainly the case that it has to be more speculative, where you're working with the government, where they perhaps haven't passed something yet. Although you can look to examples like the European Union, like India where there have been policy gains. And then certainly as far as people are interested in things like individual dietary advocacy, there have been more studies, so there have been more attempts at RCTs, so I think there's a lot more scope for RCTs in that space in terms of looking at what messaging is effective in getting people to care about these issues, and you're getting them to reduce their meat consumption.

Question: Cool. And, final question, is there progress and promise in China on the corporate pressure side?

Lewis: Not so much on the corporate pressure side. I think pressure would probably be unwise in the Chinese context, but I think we are starting to see some real progress in terms of corporate outreach, and sort of self-initiated corporate reforms. There are also various, more subtle pressures at play there. I think for instance, companies that want to export into the European market, companies that want to be seen as adopting world class standards. And so you are seeing a number of major Chinese producers now committing to get rid of gestation crates, which is something the US pork industry still refuses to do. And in some cases even to get rid of farrowing crates, which is something that the US pork industry has said is impossible. So I think we're actually seeing a lot of progress, amongst particular parts of the industry in China, less from pressure campaigns and more from sort of targeted outreach and from technical work helping these companies.