Articles

Force Multiplication

Force Multiplication

What if you could increase the output of a highly impactful individual, by freeing up their time and mental bandwidth? Alternatively, what if you could make an entire organization much more efficient in the same way? Highly skilled operations work can achieve these ends, and in fact it’s necessary for building a robust movement. In this talk from Effective Altruism Global 2018: San Francisco, Tanya Singh makes the case for being a force multiplier in EA. A transcript of Tanya's talk is below, which we have lightly edited for clarity.

Thank you everyone for coming. Today I'm going to be talking about force multipliers, and why you might try to be one. This is a big reason why I do what I do. I'm deeply bought into the ideology that you can really amplify the impact of some people who are trying to do things that resonate strongly with you, that you think are important cause areas to be working towards. Being a force multiplier to me personally is a very motivating aspect of my job. I'm going to try and explain to you what I mean by force multiplication, how can you be an effective force multiplier, etc.

The concept of force multiplication comes from military science. It refers to a factor or a combination of factors that dramatically increase the effectiveness of a group, relative to what they'd be able to achieve without these factors. While the term comes from a military science backdrop, I think the general principle is applicable to pretty much anything. Wherever there's scope to achieve something collectively with coordinated effort, wherever a group of people is trying to achieve something that is useful, that they think is important to be done, a case can be made for optimizing that initiative and effort, and to amplify its impact. Force multiplication leads to better, more efficient functioning of whatever you are trying to push towards.

I think to drive the clarity of concept, it's important to look at this thing with respect to specific cases. We'll look at two cases: increasing the impact or the influence of a group, or increasing the impact of a single individual or thought leader. I think while doing one does not necessarily mean that you're not going to be using the same practices and principles that are going to be effective with the other, it's important to try and draw out the different types of personalities that are most effective at doing these two things, either amplifying the impact of a group or amplifying the impact of an individual.

And then I think the question that one needs to ask themselves is: how do you, with your boundedly-rational self, limited abilities, capabilities, time, and resources drive that intervention, drive effective interventions that amplify the impact of the group or the individual that you're trying to support or enable.

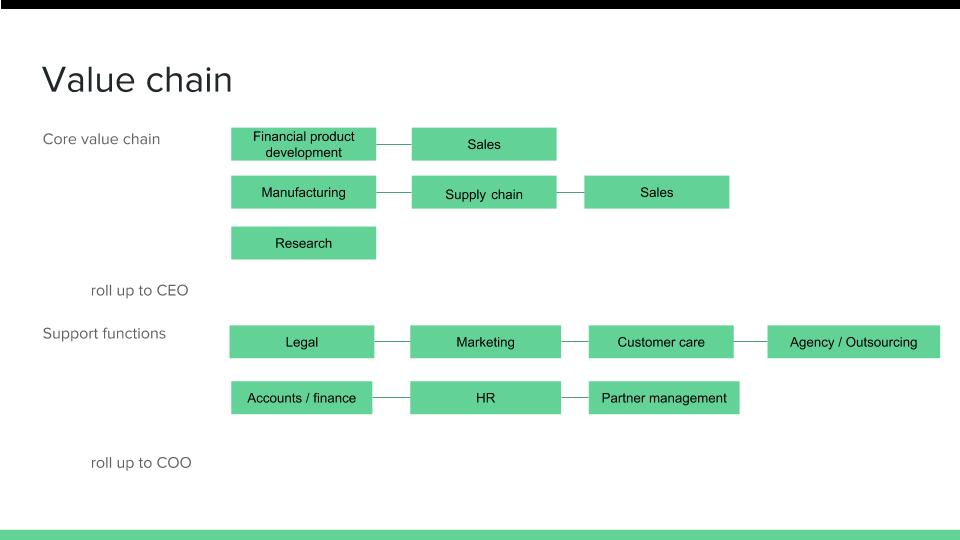

Here, I want to define and clarify the value chain of an organization, because I think in order to figure out where can you amplify impact, it's important to understand what is core to the promise that you bring to whoever you're trying to reach out to, whether with a product or a service or a piece of information that you want to put out there. And then how does your organization enable that core promise to be fulfilled or to be delivered? I think there's core value functions, and there's support value functions. But I'm going to try and take some examples and clarify this distinction.

Anything that is the actual promise of your organization, to whoever it's addressing or trying to reach out to is what I'd like to call the core value chain of your organization. If you're a financial technology company or you have a product that's finance related, personal finance related or corporate finance related, the actual product development, what that product is, what are the services and the perks that come bundled with it, and the sale of that product, getting that to the final end customer and the people who are responsible for making that sale, driving that P&L. Those are the two core value functions of the organization.

And then these functions are supported by a whole host of other important functions that enable these core value functions to actually accomplish what they are trying to accomplish. Depending on the size and the scale of your organization and its requirements, there's legal, there's marketing, there's things that feed into the product development, there's things that impact the sales like the channels you use for marketing, etc. There's human resource management. There's financial management. Bits of your work could be outsourced to partners, so you could be working with a network of stakeholders who are collectively trying to do something managing that project. All these support functions are invariably consistent across organizations. These skills are also extremely fungible. They do come with overtones of specialization that you develop once you're working in a field, but a lot of this is general experience that's very transferable across organizations, especially organizations that are working in a specific field the way all the effective altruism organizations are. They have a methodology, they have a specific agenda they're trying to accomplish, and very similar methods of getting there, basically.

To take a different example, in a manufacturing setup, the shop floor, the factory where the manufacturing happens, the supply chain that gets the product from the shop floor to the end customer as well as, again, the function that makes the sales, that handles the targets month on month, quarter on quarter: these are the core value functions. In a research organization, your research is your core value output. And everything that supports it is the enabling function. I think it's important to look at an organization not just as valuable, as important, or as iconic as its core value functions, but also as a bundle of these functions that stand on top of solid foundations of support or enabling functions, that run the show, that make things happen.

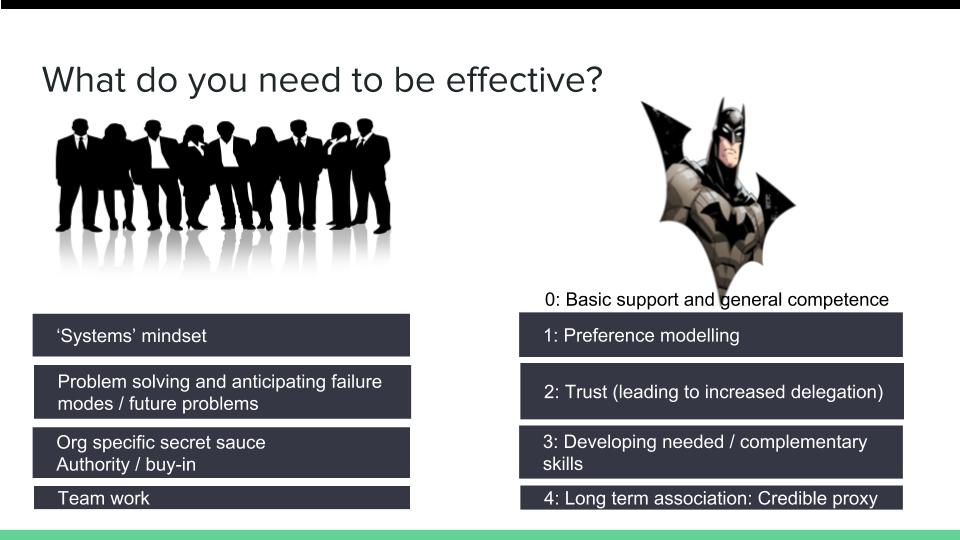

I want to talk a little bit about what you need to be effective. This is not a laundry list or an exhaustive list of what I think can be useful orientations to have, or a useful environment to have to be effective in a force multiplier role of sorts, where you can give yourself this task and come out feeling that you've achieved something meaningful. If you're trying to do this for an organization or a collection of individuals you need to, I think, have a systems mindset. You need to believe in the fact that developing scalable, robust, efficient systems creates systemic efficiencies, leading to a lot of mental bandwidth freed up, and a lot of interesting work opportunities for everyone. People don't necessarily need to be caught up doing a job which doesn't excite them, that's repetitive. People can get caught in ruts, but that doesn't need to happen if you build very scalable, robust systems and try and automate the tasks which are not cognitively very stimulating for anyone.

Having said that, at times your predicament is such that you're nested within a broader system which is out of your control. Like for FHI, we're nested within Oxford University, so we use their systems and processes, and we have to tie in whatever we develop into those pre-existing systems. At times you might be dealing with policy offices, a lot of government interaction, and they have a certain way, a methodology, and unsaid norms that you have to follow. You could be dealing within a microcosm or a macrocosm, which could be restrictive, or you could have all the bandwidth and the elbow room to do whatever you think is most efficient. But basically, you want to have a mindset that anything that's not cognitively interesting should be somewhat automated, somewhat made free of the dependence on any one individual.

You need to have the mindset of problem solving. You are going to be bombarded with a bunch of problems that are new, that you haven't anticipated before, challenges that come because the environment in which you operate changes, or the policy guidelines that impact your organization and your output change. Within this very dynamic landscape you need to be prepared for failure. You need to be able to anticipate future problems and attack them. That's not to say that you're always going to be prepared for anything that might be thrown your way. You're definitely going to get caught off guard many times. But it's good to have the mindset of knowing that, yes, things are going to break. It's going to be challenging. To know you haven't thought through something, but I'm ready to probably respond to it. It's important to know you're agile enough as an organization, having your systems in place, but still having the ability to, with agility, respond to problems that you haven't sort of anticipated before.

I think when you're trying to be a force multiplier for a group of people, an organization, there needs to be a buy-in from the organization. Between a team that's providing an enablement service and the team that's trying to achieve the core objective within an organization, there needs to be an implicit understanding of what is the service level agreement that you're willing to sign on for. How much work will the operations team commit to doing? How much mind space are they committing to free up for other people? How much is the core objective team going to share the load in terms of doing some bits and meeting the ops team midway? Every organization, because of the environment in which it operates in, the legacy systems it has, the place it wants to get to, has an implicit, tacit understanding of how all this will be handled. So getting buy-in there, having the authority to implement that and reinforce uptake of these processes that you set in place, I think that's an important thing to focus on and drive clarity on when you're working in a set-up like this.

And then of course all of this happens with teamwork. Whenever you're trying to support a group of individuals, if it's 12 to 15 people then a couple of people can do an effective job at taking care of all of their needs. It's a really challenging situation, a huge learning opportunity for those two people, but they'll be able to provide the enablement that's needed. But when your organization scales up to 50, 100, 150, it changes. Plus 500, it becomes a different game altogether. So developing solutions that scale up, that break with grace, that don't sort of crumble under pressure of scale up and change. Those are sort of important things that you need to keep focusing on, and that help make you an effective force multiplier for a group.

What do you do for an individual? I think the ability to model someone's preferences effectively to see what they need, what information they are usually looking for when they're trying to assess whether to commit to a situation or not, what kinds of questions they're invariably going to ask you, what information you need to pre collect or assess, and how best to distill that information. All these things help you develop a model of the person that you're working with, working for, whose impact you're trying to amplify. You get feedback on the model, in a sense. You see whether your predictions are accurate, inaccurate, how can you refine them, fine tune them a little more. I think that's where you start.

It's interesting because I was talking to Nick about my presentation, and he said, "Well, there's a level zero, which is basic support and general competence and how he said that was, 'not making a mess of things,'" so not going and mucking everything up is also extremely important. It starts there, and then you develop a bit of a rapport. You develop a model for the preferences of the person you're trying to work with. And you feed that information back to them. I think that's where the importance of preference modeling lies. You give them the confidence that you're doing a decent job at accurately representing their beliefs, accurately representing their requests and requirements, so that they start delegating more things to you. Getting that authority, taking that cognitive load off their plate, giving them more time to engage in things that ostensibly they should be doing, that they're much better at doing. I think that's where real value is uncovered in, when you're trying to support an effective altruist leader of sorts, or a thought leader who you really want to amplify the impact of.

I think at the third level you start developing complementary skills, things that are needed. So if you're supporting someone who's writing a book, you would be able to add a lot of value by understanding what are the best ways of digitally marketing a product in today's world. You don't necessarily have to build all the skills yourself, but you need to have enough subject matter knowledge in order to work with experts, in order to collaborate with people you hire on retainer or people you hire for a one time project to do any of these things. If the person that you're aligned to is not a great networker but could benefit a lot from meeting certain individuals, being part of some conversations, then how do you in your capacity enable and facilitate those meetings, those connections? And if you're not good at it, how do you leverage the network around you in order to achieve that end outcome? I think that becomes the level three of operating while being the force multiplier for an individual.

And then I think there are some things that get unlocked. There are levels that get unlocked only after long-term association, after a lot of trust has been built, after a lot of challenges, situations have been conquered, observed together, the problems that you face together. And then after that, not only the person you're aligned to and yourself, but other people start seeing you as a credible proxy who can stand in for that person's judgment, for that person's viewpoint on something. And I think that's where you truly free up a lot of mind space, a lot of long-term impact opportunities, that are unlocked when you reach that stage.

I also want to call focus on some critical features for a person to have, who's trying to be an effective force multiplier. I think if they have these things, they're poised for more success than they would have without them. Again, this is not exhaustive. 80,000 Hours' ops post has a whole section on the mindset, the skills that you'll want to be calling out for, focused on, holding, et cetera. I'd recommend everyone read that.

I think value alignment or mission focus to me is something that's extremely important for an operations person, or for a person who's trying to amplify the impact of an ideology in the world. This is not to say that value aligned people have it easy, or that it's all fun and games and excitement. Your job can get really hard at times, and it can get really challenging. But if you're value aligned, and you're deeply bought into the mindset and the ideology, then the challenges and the failures and the setbacks won't lead you to question your life choices, in the sense they'll still hurt, and they'll feel bad, and you'll be driven to improve all the good things that will come out of it. But you will not feel, "Should I be doing this? Should I be doing something else?" I think that whole element goes away, and it leads to lasting satisfaction. So I cannot stress the importance of this more.

The drive to upskill and learn. There needs to be some people in the organization, or any movement, who are ready to chew on glass. And I don't know how to more delicately put this, but there are things that not everyone wants to do. But some people need to be committed to doing those things in order to make sure that important things happen. The movement gets the wind it needs beneath its wings because there are people who are doing the not so glamorous but super important things.

I thought a bit about how to position this vicarious orientation that I want to point out. For a community that cares about aligned artificial general intelligence, not everyone can be an AI safety researcher. It's not even effective if everyone is an AI safety researcher. So there need to be people who know that, "Okay, my strength is networking or my strength is project management or my strength is putting together great events like this where people can come together and actually talk." So playing to your strengths, identifying where you can contribute, where you can have the maximal impact, and committing to do that while knowing that you're freeing up time, mind space, energy of people who are really good at solving the kinds of problems that you're worried about. I think that sort of an orientation helps. Looking at things like that is useful when you're trying to be a force multiplier.

And then whether you're a team player or you're an individual contributor, however you see your strengths, I think there's a place for you if you are trying to support a team of 10s of people, you're part of a tightly knit unit that's committed to providing a certain level of service across all the processes that people have to engage in. Your responsibilities are divided among three, four people of a team. It's a team effort, which fails together and succeeds together. So I think if you're a bit of a team player, which is a very useful important orientation to have when you're trying to support an organization, trying to be a force multiplier, trying to commit to a cause, trying to commit to doing things that are sort of non-glamorous, then there's a place for you there.

If you're an individual contributor, you sort of thrive a little more if you're given more elbow room to flourish and explore things, which is not to say that you don't have to have the skill, the ability to manage relationships and communicate effectively with a lot of people. Those are hygiene skills that everyone needs. But if you need a bit more elbow room to flourish, then trying to explore opportunities for being a project manager, a personal assistant, an executive assistant to some high impact individual is, I think, something that you would find very interesting.

Lastly, I want to talk a little bit about what do you gain from this experience? I think the biggest thing you'll gain by supporting an organization, trying to amplify their impact, is how to run an organization. Like, how to run complex projects with multiple stakeholders, how to firefight things that you haven't anticipated, that you're not prepared to deal with, and that's a very useful skill in movement building, organization building, trying to accomplish something where a lot of people with different levels of buy-in, different levels of commitment to different things that are important to the cause come together.

Navigating those complex waters is a very important skill that you get to hone and develop wholly. You develop a great understanding of the lay of the land that you're dealing with. You get connected to all the important people. These are small communities, a few people coming together to do all sorts of interesting and important things. They send leads, whether it's media engagement leads or leads of other policy makers along each other's ways, so you get to interact with everyone who is important in the community, build your network, see how you can facilitate these interactions given your strengths and your understanding of the field.

And then you get to develop your career capital by focusing, if you're interested, either in specialist skills, figuring out how best to give grants, how best to put up events of this scale and nature, or double clicking on marketing. Whatever interests you, or you can keep developing these broad generalist skills of people who are effective at running organizations, complex movements, helping facilitate communication and growth of the whole community.

Analogously, when you're talking about doing this for an individual, you get to model an effective altruist leader, and you get to be their sidekick. And if the word sidekick is slightly offensive to you then substitute it with whatever you're excited by, but what I mean to say is that without having the actual responsibility on your head, you're living the life of someone who has all these amazing opportunities knocking at their doors all the time. The kind of things that you get exposed to are people wanting advice on what to do with their company, what to do with their funds and resources that they've unlocked. A lot of policymakers, government people, NGOs knock on your door trying to understand how would you react to a particular recent development in the field.

These are exciting times, and effective altruism is full of people who are extremely well reasoned, thoughtful thinkers who a lot of people want to listen to and get advice from. So there's a lot of opportunity to do very interesting stuff, and you're only limited by your own bandwidth, your capacity to commit to different types of projects and deep dive into them. Obviously you get to pick what you like. You get to identify niches for yourself where you're like, "Maybe I want to develop this skill more. Maybe I already am good at it, and I can really make a difference to this project." So you get to pick the projects that you like.

Some people, Laura as an example, is doing amazing work with Will MacAskill. She's Will's project manager, and he gets a lot of requests for, "Where should I invest my money?" Or where to distribute these funds that we have in order to promote this sort of thinking in academia, building a systems mindset that we're thinking about for these cause areas. I think those are extremely interesting opportunities where she has to learn, she has to upskill, she has to talk to a lot of people, put herself out of her comfort zone quite periodically, and upskill in order to understand what's the best advice to feed to Will who has limited time, limited energy.

I think I've spoken a bit about this. You aid decision making. You can develop credible models for effective communication between these leaders, between the people that they're trying to reach, and the people who are trying to reach them. And you can truly, I think, have a huge impact in how you facilitate this whole process. I think it's important, this message that I'm leaving there, which I would like you to take in the spirit that it's intended. Highly impactful people or organizations always have a whole host of force multipliers behind the scenes. Any CEO has a group of people who make magic happen, from writing amazing speeches, to coordinating their traveling logistics very efficiently, to figuring out how should they spend their time, how should they bunch up their preferences, all of these things.

Areas of maximal contribution and impact that you can identify are, Kyle Scott has a list that he shared in the operations forum of people who do not have either executive assistants or research assistants or project managers, and who arguably should. They absolutely should. There are many people in the community who, if you can support, it will be a hugely impactful thing to be doing. All the operations roles that are open and that tend to stay open for a really long time until the time that some academic commits to doing them, until the time that we can find an ops person, and all those roles are extremely important. They need people who want to be doing these things and are excited about doing these things to be doing them. There are lots of opportunities if you want to try out, if you want to contribute.

It's not easy to do these things that should magically happen. It's also not non-rewarding. At times I've said things like this or at times I've heard in the heat of the moment you feel that, "Is this rewarding? Should I be doing everything that other people arguably don't want to do or else they would've done it themselves?" I think it can be super rewarding, because every day you're responsible for things. If you're the kind of person who likes knowing that being involved in a situation is actually leading to some positive impact, positive change, well, you will be in a lot of situations where you're the last person responsible for those things. It makes you responsible. It's hard because you're emotionally invested in what you're trying to do. You care deeply about the outcomes and the objectives that you're trying to achieve. And it's extremely challenging because you know the opportunity cost of failure. You know the trade-offs that you're trying to make and the research time that you lose, or the energy effort resources that you lose if you muck things up.

Being all this, it's also extremely awesome because you're in the eye of the storm. You're in the vortex where everything is happening and hopefully happening well. I think that our preference biases that everyone has for being on the forefront, being the icon, and I think this field has a little more of that. Like I've observed a lot of this orientation where everyone wants to be an icon in the field rather than being okay with being the sidekick. I think the movement can be turbo charged if there are people who understand that the forefront, or what you consider maximally impactful, is a bit of an illusion. The benefit of hindsight lends you that knowledge that okay, this was actually the most impactful thing. Be good, do good, find the people who are doing the kinds of things that you think should be done and try and contribute to it the best that you can. Thank you.