Articles

Open Philanthropy Project Biosecurity Update (2018)

Open Philanthropy Project Biosecurity Update (2018)

The Open Philanthropy Project pursues charitable interventions across many categories, of which a major one is global catastrophic risk mitigation. Claire Zabel, a program officer for Open Phil, gives an update on their recent work and thinking about biosecurity. This talk was recorded at Effective Altruism Global 2018: San Francisco. A transcript of Claire's talk is below, followed by questions from the audience.

The Talk

Thanks everyone so much for coming. It's great to see more EAs getting interested in biosecurity, although our numbers are still few, they're hopefully growing. The program in biosecurity at EA Global is much more extensive this year than it was in the past, and I'm really happy to see that. I'm happy to talk to interested folks about this kind of thing.

I'm a program officer in global catastrophic risks. I spend about half my time in biosecurity right now. Specifically, when I work on biosecurity, I'm thinking about it in the context of global catastrophic biological risks, by which we mean, in case you haven't heard that term before, risks that could, if they occurred, have the potential to derail or destroy human civilization in the long-term. And so when we think about biosecurity, we're thinking about it in the context of our efforts to make sure the long-term future is good, as opposed to focusing primarily on efforts to help people now. Open Phil does more to help people now through our programs in US policy, as well as global health and development.

I've been thinking about bio in effective altruism and effective altruism in biosecurity a lot this year, and I want to share a few of my thoughts on that topic. I'm going to try to communicate some of what I've learned and done this year, focusing on some recent projects. I've kind of split this into some projects, and sort of analysis areas, which is a soft term I'm using for things that I've been thinking about that I think are important for people who are interested in this space to keep in mind, and some of what I've learned from that. These are examples. They're not comprehensive lists of what I've done or been thinking about. I selected them because I thought they might be of interest and I'm definitely going to try to leave time for questions.

The first thing I want to talk about was our project in early-career funding. Our idea was to fund grad programs and internships in fields or in organizations related to biosecurity, with the goal of helping to get people who are relatively value aligned with our view on biosecurity, who are interested in global catastrophic biological risks in particular, have an easier time moving into that field. We also wanted to help them make the transition potentially more quickly. Give them more time to do work without having as much a pressure from other needs, like financial constraints.

We've accepted six applicants and I'm really happy with what all of those applicants are doing. Happy to see actually some of them in this crowd. Congratulations! We haven't announced it quite yet because one person is still deciding, but we're going to announce that later. Right now we're thinking about whether to renew that program. We're just considering it. We're really curious for feedback from other people on whether that would be a helpful thing for them. Something that would help them do something related to global catastrophic biological risks quickly or earlier, or not. We're not very clear on the extent to which money is or isn't a limiting factor in this. We also are kind of worried about over-pushing a career path that we don't yet understand very well and that we're not sure is the best one.

There's a kind of risk that I'm holding in my mind that our funding in the space could be taken as a strong endorsement of certain routes or paths, and we're not sure that those are the best paths. So we want to be wary of that tension, and we want people to go out and explore, and we want to learn more about how people can have an impact in this space, but it doesn't feel like something that we're highly certain about. And this feels connected to a later topic I want to discuss, which is sort of what's EA's niche in biosecurity? I think that there are a lot of possible answers to that question, but I don't think that we're yet at the stage where we can have solid conclusions about it.

The second project is a write-up on viral pathogen research and development. Most of this work was done by our program officers in scientific research, who I have little pictures of: Heather Youngs and Chris Somerville. This was a medium-depth investigation into the space, and it focused a lot on antivirals and vaccines. We did this because we really wanted to learn both about the space in general and about whether there might be good funding opportunities available to Open Philanthropy when we dug into it more deeply. And so, some kind of quick takeaways from that; I thought it was really interesting what we learned. The most interesting part, I think to me, was just this idea that there are many novel vaccine types, and that those may or may not bear fruit in the future, but that we couldn't identify a lot of really hard scientific barriers to making very fast effective vaccines.

I expect that some might well exist and that also many logistical difficulties that aren't related to hard scientific barriers might exist. But it seems sort of like a ripe area for further learning and experimentation to figure out what we really need to do before we can be more likely to create very fast vaccines in the event of an emergency. Perhaps one involving an awful novel pathogen against which we don't already have treatments. We also looked a little bit into antivirals and found that they've in general received a lot less attention recently. One theory about why this is would be that antivirals are less useful to some extent in the developing world, where people have irregular or low access to hospitals and health care professionals, because you kind of need to take antivirals quickly right around the time that you get infected with a virus. And then also, some of them are not hugely efficacious against a broad range of viruses. For that reason we thought maybe it was a little bit under-explored, and there might be opportunities there.

In particular we looked at chaperone inhibitor proteins. Chaperone proteins are proteins that help your body fold new proteins it's creating into the right shape. So they kind of like "chaperone" them into being the right form to be functional. And inhibitors obviously inhibit that process. That sounds like a bad thing, because you obviously want your proteins to be functional. But we thought that it could have a potential for helping deal with viruses, because viruses also are hijacking your body's machinery to fold their proteins into the right shape. And if you could inhibit that process it might reduce the amount of viral replication. Of course, that would have some side effects, so it's probably not something that would be worth it to do for something like the common cold.

But there's a little bit of evidence from cancer patients that the side effects might actually not be so severe and they might be worthwhile if you were, for example, infected with a very potentially deadly virus. We also have funded this research in David Baker's lab, and he's attempting to make a universal flu vaccine, which is definitely a long shot, but it's something that would be really amazing if it succeeded, because flu is both surprisingly deadly, killing lots of people every year, and also one of the viruses with the potential to maybe mutate into an even more deadly and dangerous form. In the flu virus, there are these kind of outer parts, which is what your body usually recognizes and tries to fight off. And then it has these inner parts that are highly conserved across many different strains of flu. So the outer parts are mutating rapidly and are different between different flu viruses. This is an oversimplification, but approximately true, and then these more inner parts are more conserved.

The idea is if you could get your body to be exposed to these inner parts that it's not normally exposed to, then it might be able to actually be immunized against many different types of flu, as opposed to just developing immunity to one type of flu, and then it mutates and then it no longer has immunity. So he's trying to create these proteins that have those inner parts more on the outside, and where your body can potentially induce production of broadly neutralizing antibodies, which are antibodies would neutralize many different strains of flu. So we're interested in that research, like with most of our scientific research funding, we think there's a good chance that it won't come to anything, but it's part of our philosophy of hits-based giving to, when we think a long shot could be worth it, try to give it support nonetheless.

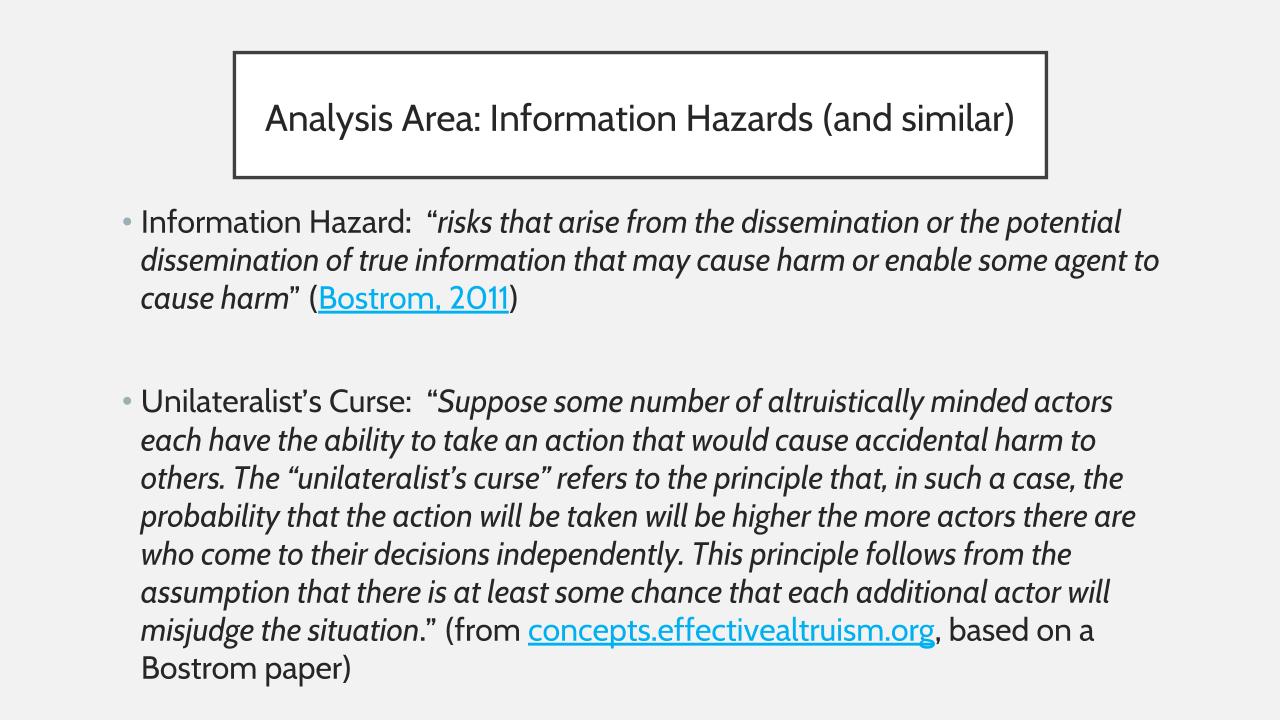

Now I want to talk a little bit about the different areas of analysis I've been thinking about that are specifically related to involvement in global catastrophic biological risks, and are kind of common concerns I think especially in the EA space, and ones that I would love to get more people thinking about. So I think the first one I want to talk about is Information Hazards and the related Unilateralist's Curse issue. I put some definitions up here that maybe you guys could just read really quickly while I have a drink.

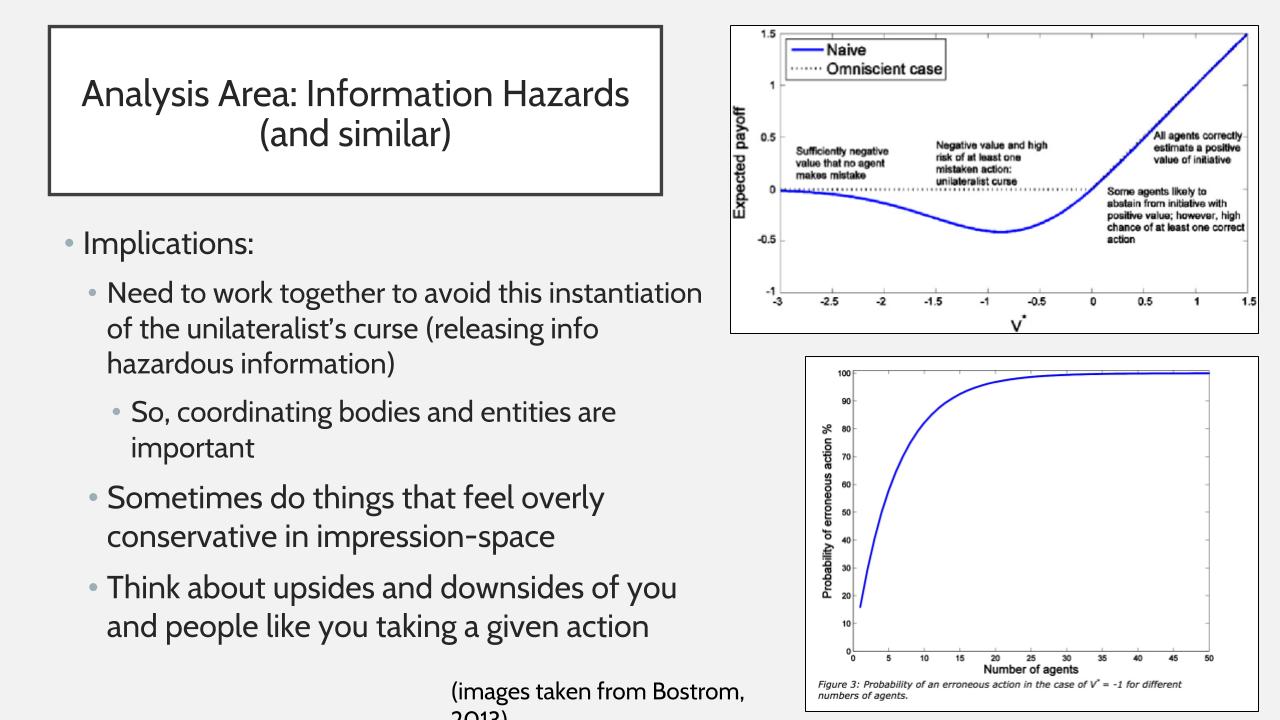

The definition of Information Hazard is risks that arise from dissemination or the potential dissemination of true information that may cause harm or enable some agent to cause harm. This concept was coined by Nick Bostrom. The Unilateralist's Curse is the idea that if there's lots of actors, even if they all have good intentions and they all have the ability to take an action, we should expect that even if it's a bad action, some of them might wrongly think it's a good action and take that action. And so overall, with sufficiently large number of actors, it becomes fairly likely that an action will be taken, and if that action is something like a publishing a piece of information then it really only matters if one person does it. That's basically as bad as lots of people doing it because once it's on the Internet, then anyone can see it. This is also a Bostrom concept. Bostrom is very interested in these types of concepts. Here's some little graphs that might help illustrate them.

And so I think these are important concepts for people who are interested in work in biosecurity, especially in the EA community. The EA community, really, I think people love to work together and talk about things online, hash through tough concepts. And I think that's one of its best qualities actually, but I think this is an area where we need to be a little bit more circumspect about some of that and a little bit more careful. So that's why I wanted to highlight it. I think that we need to kind of work together, and sometimes I think being aware of these concepts will involve doing things that feel overly conservative to you according to your feelings. But if you're never doing something that feels overly conservative to you, then you might be falling prey to this, this kind of curse idea.

A real example in my mind, in my actual work, is that there's a person with whom I really want to share a certain document and I really think it would be great to share this document with this person. They're really smart, they could be a really great ally, and I think that the downsides are minimal. I don't think they're going to do anything inappropriate with the information. But a key adviser of mine really doesn't agree with that and I really respect that person's judgment. And so even though in this particular instance, it kind of feels silly and excessive to me, I'm not going to share this document with this person until my adviser changes their mind, or if they don't change their mind, then I won't ever do that. And the way I think about that is if I released info every time I felt like it, soon enough I'd probably make a mistake. And if everyone did that, then we would really only be as safe as our least cautious person, which feels like a pretty bad place to be in.

I think that this is an area where coordination around these concepts is important. Especially in the beginning, when we don't totally know what we're doing, we're still figuring things out. It's pretty good to err on the side of conservatism and not do anything irreversible. I think when you're taking an action you should just think about the upsides and downsides, not just of you, but of all the similar people like you having a similar policy. Does that, in expectation, add up to disaster? If so, don't do it. But I also want to highlight that I don't think there's an easy answer here and too much conservatism itself has really negative impacts. It makes it really hard to recruit. It makes it hard for people to understand what they should do and prioritize within the space. And it's harder for people to take up and make informed decisions. It takes up a ton of time and energy thinking about it. So I don't think just like, "be super conservative" is a good policy either. We actually just have to figure out how to walk a really tough line and strike a really tough balance. But we should do that in a coordinated fashion because if we are all striking our own balance that won't be very efficient.

Last, I want to talk about just some thinking on EAs and biosecurity and where we may or may not have a niche. And I think focusing on global catastrophic biological risks in particular, both fits with a lot of our values and might be an under-explored area. I think thinking about what efforts might be broadly useful is a good thing to do, especially things that are only useful in the event of a really bad emergency. The antivirals that I was talking about recently are a good example of that. Things which are not normally useful for more day-to-day issues might be under-explored by people who are focusing mostly on those day-to-day issues. So if you kind of think about what in particular is only useful in a worst-case scenario, that might be a fruitful avenue of inquiry.

Other broad areas are things that address state risk, risk from states, or risks from a synthetic biology on the cutting edge areas where there's not a lot of precedent, there's not a lot of pressure on most people in government to work on those because they haven't yet occurred or people don't know about them. There's not a lot of public pressure, but they also could potentially lead to greater catastrophes than what we see coming out of nature. But I think a lot more work is needed to outline these career paths. As I said, thanks to those of you who are working on this and helping with this because I think it's just really valuable and hopefully we'll have a lot more specific information to say next year.

The last thing I want to say is just there's kind of longish timelines working in this space, and so patience here is a virtue. It might be good to start thinking most early on about the distinction between technical work versus policy work. Kind of a la AI, if you are following work in that space, because maybe that might determine whether you want to go into a more bio-science focused PhD or other grad program versus learning more about policy. Although my sense is that starting out in the more technical area is the kind of option preserving strategy because it's easier to switch from technical work to non-technical work, than non-technical work to technical work, based on what I've heard from people I've talked to.

Some EA orgs are focusing on expanding their work on this. FHI and Open Phil are the most obvious ones. We're trying to learn about this a lot. We might expand our teams. And so I think helping with that could be an amazing option for those of you who are interested. But other than that, I think that we should all think of this as a nascent area that's still in flux in information, where we might be changing our advice next year. We might think that different things are valuable next year and people who are sticking with it are functioning as these forward scouts, helping us understand what's going on, and it's not yet a mature area. And so I'm really grateful again to everyone here who's helping with that.

Questions

Question: How neglected of a field do you think biosecurity is currently, especially compared to other cause areas such as AI safety and nuclear security, how do you see Open Phil fitting into the space, and how do you see other young, motivated EAs who want to enter this space?

Claire: That's a really good question. I think it's still something we're trying to understand. I certainly think if you took like, number of people who would identify as working in biosecurity or millions of dollars that are identified as going to support efforts in biosecurity, it would be much, much higher than the same numbers would be in AI or AI safety. I'm not sure about nuclear security. My sense would be that that would be even bigger, although maybe Crystal would know more about that.

But I think that the relevant question here is to what extent is existing work on biosecurity relevant to global catastrophic biological risk? I think that that varies depending on the specific intervention or type of effort that you're looking at, but I do feel like our early forays have indicated that there are some areas that might be pretty neglected that are mostly just relevant to global catastrophic biological risks. Like in AI, it feels like there's a lot of work to be done and there's a lot of low hanging fruit to us right now. That's not a very concrete or quantitative answer to the question, I'm more just reporting my sense from looking at this. But I think it would align with what other people who have been doing this, like the folks at FHI, think as well.

Question: It seems like Open Phil is very interested in looking at global catastrophic biological risks. What has the response of the biosecurity community been like with these interests that you guys have?

Claire: Yeah, it's a good question. It would be a better question for Jamie, our program officer in biosecurity who specializes in this and has done a lot more for the grant making. My sense is that a lot of folks have really become interested in it and have been very open. I've definitely seen a lot of an engagement starting to come out of that community. For example, the Center for Health Security had a special issue in their journal Health Security on just global catastrophic biological risks, and a lot of people submitted articles to that.

I also think there's also a lot of people who are more skeptical, and have an intuition, that I think is very reasonable and comes from a very good place, of being worried that we'll distract from efforts to help people who are really suffering right now. That we have these very speculative concerns that may or may not be justified, may or may not come to anything, and that may conflict with the moral intuition that it's really important to help people who are in need right now. So maybe those people are worried about distracting or diverting money from pressing current issues to work on more speculative goals.

Question: I get the general sense that technical work is more prioritized by the EA community in AI safety, whereas policy or strategy work seems more promising in biosecurity. Do you agree with this, and what do you think is the reason for this distinction if true?

Claire: That doesn't really align with my impression of how at least some people are thinking about AI safety. My sense is that some people think that AI policy and strategy work is actually maybe in higher demand, or the marginal value of a person going into policy might be higher than the value of a marginal person going into AI safety. But I think that would vary a lot depending on who you talk to. For biosecurity, I think that it's really too early to tell. I wouldn't make a statement. Definitely feels like when we make lists of the best seeming projects to us, some of them involve more technical work and some of them involve more policy work. I also feel a little bit uncomfortable with this policy/technical distinction because working on policy can be extremely technical.

I started it, so it's my bad, but I was more thinking of working on science and engineering versus working on implementing policy or governance strategies. I don't feel like we really have a strong view about which one is more valuable. It just seems like for younger folks who are still figuring out how to start out, it's easier to switch from the science-y to the non science-y rather than vice versa. And so that's sort of a more robust option.

Question: The concept of personal fit seems to come up a lot in EA discussions. Do you have any suggestions or recommendations about how a young motivated EA might test if this field is a good fit for them, or are there reasons why they might be more well suited to working in biosecurity than some other GCR issues?

Claire: Yeah, it's a good question. So first on personal fit, I agree, personal fit is really important. I think people are immensely more productive and more likely to think of good ideas when they're enthusiastic about the area and they find the area interesting. So definitely plus one to that. As to how to kind of test that out, I don't feel like there's an established good way to do it. Doing something like an internship at an organization that works on biosecurity seems like a pretty costly but hopefully effective way to test out fit. Although I could still imagine getting the wrong project and not feeling like it clicks, when maybe if you were given a slightly different project, it would click more.

For someone who's earlier on and doesn't want to do something that costly, I think going through the resources that are available on global catastrophic biological risks and seeing if they seem interesting to you. Reading through them, and seeing if it feels like you are curious to learn more and you would love to learn more, or it feels like there's an open question and you're like, "Oh man, it didn't address this issue, but what about this issue? I'd love to figure out that issue." That would seem like a pretty positive sign of personal fit to me. But I think that's just like, me theorizing about stuff. That's not like a time tested strategy.

Question: Do you see organizations in the spirit of OpenAI or MIRI starting up in biosecurity anytime soon, and if so, what do you envision them doing?

Claire: So I'm guessing the more generalized question would be like, are there going to be organizations dedicated to global catastrophic biological risks that maybe try to do technical work on reducing the probability of one of those events occurring? And new organizations as opposed to existing organizations that do some work in that space. Although OpenAI also does AI capabilities work. I would say I think there's some prospect that that might happen, but not super short term plans for it to happen. But I think that something like that would be pretty impactful and useful if that happened in the next few years.