Articles

Karolina Sarek: How to do research that matters

Karolina Sarek: How to do research that matters

Why is it that some high-quality research fails to affect where we choose to direct our time and money? What makes other research more persuasive or actionable? In this talk, Karolina Sarek, co-founder and director of research at Charity Entrepreneurship, discusses techniques for producing impactful, decision-relevant research.

Below is a transcript of Karolina’s talk, which we’ve lightly edited for clarity. You can also watch it on YouTube and discuss it on the EA Forum.

The Talk

What makes good research? Having worked as a researcher for academia, nonprofits, and for-profits, I repeatedly observed something that not only struck me, but ultimately led to a career change: In spite of the countless hours that went into research, not that much changed. There were no major updates, no strategy changes. Research efforts didn't necessarily transform into actual units of good. There was a big gap between research and decision-making. So I started wondering why. What makes good research?

I decided to pose this question to a group of professionals working on the methodology of science, and I heard that good research:

- Needs to be published in peer-reviewed journals.

- Is high-powered and has big sample sizes.

- Is valid and captures what it set out to capture.

- Comes from non-biased sources of funding and non-biased researchers.

- Presents precise results.

I think that all of those qualities are extremely important. Sadly, they're also true for these studies:

As amusing as this is, I think we all agree that exploring those topics is not the best allocation of our limited resources. But I also think that common measures of research quality are not getting at what we, as [members of the effective altruism community], care about most. They are not focused on increasing the impact of the research itself.

So even though I knew the qualities of good research, again I saw this gap between research and decision making. But this time I decided to change that. Instead of just asking questions, I co-founded Charity Entrepreneurship, an organization that not only conducts research to find the highest-impact areas to work on, but also immediately finds people and trains them to start high-impact charities. They're implementing the interventions that we find to be most promising.

Now I'll tell you what I've learned in the process. I'll tell you about three main lessons that I apply in our research — and that you can apply in your research as well:

- Always reach conclusions through your research.

- Always compare alternatives with equal rigor.

- Design research to affect decision-making.

I'll explain what the current problems are in these three areas, show you examples, explain why they happen, and provide solutions to address them.

Lesson No. 1: Reach conclusions

Imagine that you have a crystal ball. Instead of telling you the future, it tells you the answer to any question you have, including your research questions. And you're 100% sure it’ll tell the truth. Would you ask the crystal ball all of the research questions you have to avoid the effort of doing the research in the future?

I think if we could, we definitely should, because the main goal of conducting research is the destination — the answer we get — not the path for getting there. And in my view, the ideal research is not beautifully written and properly formatted, but provides the correct answer to the most important questions we have.

I know that in the real world, we don't have a crystal ball, and we need to rely on strong epistemology and good research processes. But we also need to remember that the main goal is to get the answer — not to follow the process.

If we fail to reach a conclusion, there are three major problems:

- The research won’t have any impact. This is the most important problem. We might not utilize the research that has been conducted and it might not affect decisions or change anything.

- [Failing to reach a conclusion may result in] redundant research. When research ends with the statement “more research is needed,” we very often must [review] the same facts and considerations [as a previous researcher], but this time [reach] conclusions by ourselves.

- Others might draw the wrong conclusion. What about a situation where your audience really wants an answer? Maybe they’re a funder who is thinking about funding a new project or organization. If you, as the researcher, do not draw conclusions from your own research, in a way you're passing this responsibility through to your audience. And very often, the audience has less knowledge or time to explore all of the nuances of your research as a whole, and therefore could draw worse conclusions compared to those that you would.

These problems became apparent to me for the first time when I was following the progress of golden rice. Golden rice is genetically modified to contain vitamin A to prevent malnutrition, mostly in Southeast Asia. The Copenhagen Consensus Center stated that implementing golden rice in agriculture was one of the biggest priorities [for the country of Bangladesh]. And in a 2018 approval, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration stated that the level of beta-carotene in golden rice was “too low to warrant a nutrient content claim.”

You can only imagine what that did to public opinion about golden rice. You could see headlines like “‘Genetically modified organism (GMO) golden rice offers no nutritional benefits,’ says FDA” and “FDA says golden rice is not good for your health.” But here's the catch: It’s true that it offers no health benefits — to Americans. In order to claim that food is fortified with a specific vitamin, companies must include a specific amount, based on a typical American diet. But a typical Southeast Asian eats 25 times more rice than a typical American. Therefore, the beta-carotene [in golden rice] is sufficient for a child who is growing up in Bangladesh with a vitamin A deficiency, but doesn't provide any health benefits to Americans [who eat much less rice]. This shows that the conclusion we draw needs to be relevant to the decision that is actually being made.

Fortunately, the FDA adjusted their statement and provided supplementary conclusions to help guide the decision of Asian regulatory bodies. As a result of that effort and many other actions, golden rice was approved and released in Bangladesh in 2019. The story has a very happy ending, but before [that happened], 2,000 children lost their lives, and another 2,000 became irreversibly blind, due to vitamin A deficiency [numbers which likely would have been lower if golden rice had been introduced earlier].

That shows how important it is to come to a conclusion, for the conclusion to be relevant to the decision being made, and of course, for the conclusion to be correct.

So, what stops us from drawing a conclusion? First of all, we might be worried that there is not enough strong, objective evidence upon which to base our conclusion. We might introduce too much subjective judgment or moral reasoning, which might not be generalizable to [others’ views]. Second, there could be too much uncertainty to propose a conclusion. We don't want to spread incorrect information. And finally, we could be worried about stating the wrong conclusion, which could lead to reputational damage — for us personally as researchers, and for our organization.

There are a few solutions to [these obstacles]. If you don't have a conclusion, then you can distinguish your subjective models from the objective ones. Maybe you're familiar with how GiveWell does their cost-effectiveness analysis, splitting subjective moral judgments about impact (for example, saving lives) from objective judgments based on the actual effectiveness of specific programs or interventions. Of course, in the end, you need to combine those models to make a hard decision, similar to how GiveWell makes such decisions, but at least you have a very clear, transparent model that [distinguishes between] your subjective judgment and the objective facts.

A second solution is to state your confidence and epistemic status. If you're uncertain when conducting your research and can’t draw a conclusion based on the evidence at hand, you can just state that the evidence is not sufficient to draw a conclusion.

Additionally, I think it's definitely worth including what evidence is missing, why you cannot draw a conclusion, and what information you would need in order to come to a conclusion. That way, if somebody in the future is researching the same topic, they can see the specific evidence you were missing, supplement your research, and come to a conclusion more quickly.

And the last solution I’ll suggest is to present a list of plausible conclusions. You canstate how confident you are in each possibility and [explain what missing information] could change your mind about it [if you were to learn that information]. You're just expressing the plausible consequences of your research.

And what if you actually do formulate a conclusion, but are afraid to state it? I would hate to be responsible for directing talent and charitable dollars to another PlayPump-type charity [PlayPump concluded too early that a certain type of water pump would be very useful to villages, only to find that older water pumps actually worked better].

However, if we slow down or fail to present our true confidence until we are more certain, then we sacrifice all of the lives that have been lost while we’re building up courage. And the lives that are lost when we slow down our research [matter just as much] as those lost when we draw the wrong conclusion.

Lastly, we can build incentive structures and [refrain from] punishing those who come to incorrect conclusions in their charitable endeavors. As long as the method they used was correct, their research efforts shouldn't be diminished in our eyes.

Lesson No. 2: Apply equal rigor to alternatives

The second lesson I've learned involves comparing alternatives and applying equal rigor to all of them.

The first problem with comparison is that there's a lot of high-quality research out there. Researchers might be [exploring] the effectiveness of an intervention that hasn’t been evaluated before. Or maybe they’re assessing the life or welfare of a wild bird, or a harm that could be caused by a pandemic [see the next paragraph for more on these examples]. Even though the research might be very high-quality and [capable of providing] in-depth knowledge and understanding about a given topic, we might not be able to compare [the issue being studied] to all of the alternatives.

For example, what if we know that the intervention we evaluate is effective, but not whether it’s more effective than an alternative action we could be taking? Wild birds suffer enormously in nature, but they may not suffer more than an insect or a factory-farmed chicken. A pandemic might be devastating to humanity, but is it worse than a nuclear war? And I know that this point may sound like effective altruism 101 — it's a fundamental approach for effective altruists — but why isn’t there more comparable research? Not having comparable research can result in taking actions that are not as impactful as an alternative.

The lack of comparison is not the only problem, though. We also need to look out for an unequal application of rigor. Imagine that you are trying to evaluate the effectiveness of Intervention A. You're running a very high-quality RCT [randomized controlled trial] on that. And for [Intervention] B, you're offering an expected value based on your best guess and best knowledge. How much better would Intervention B need to be in order to compensate for the smaller evidence base and [reduced] rigor? Is it even possible?

We might think that we are comparing costs or interventions in a very similar manner, but in fact, they might not be cross-applicable. For example, we could have been looking into one intervention for a longer period of time. We [would thus have had] time to discover all of the flaws and problems with it [making it look weaker than an intervention we hadn’t examined for very long]. Or the intervention might simply have a stronger evidence base, so we can pick specific things that are wrong with it [it can be easier to criticize something we know a lot about than something we’ve barely studied].

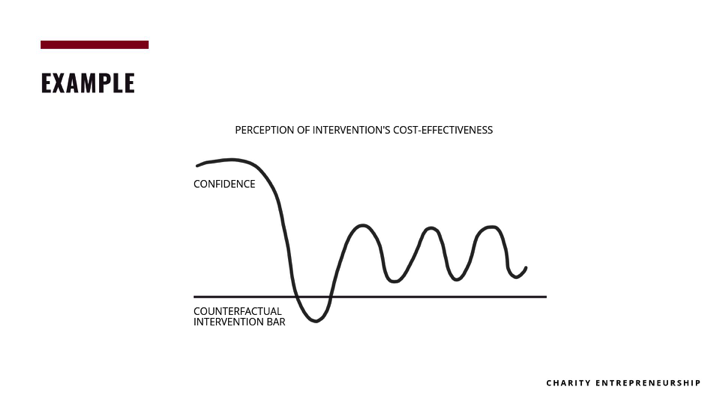

I think the perfect example is something that I’ve observed in almost all of the charities that people started through the Charity Entrepreneurship Incubation Program. Basically, when we first suggest a charity idea, participants are extremely excited and confident. They feel like it’s the highest-value thing for them to do, and are like, “I'm going to spend my life doing that.” But they start researching the idea and their confidence drops. Maybe they discover that it's harder than they expected, or the effect was not as big as they had hoped.

However, the moment they start looking into alternative options, they realize that the alternative charity that they want to start, or the completely different career path they want to go down, has even more flaws and problems than the original charity idea that was suggested. In turn, their confidence recovers. And fortunately, most of the time, they do reflect and apply equal rigor, and the higher-impact charity wins and gets started.

However, imagine a situation where that’s not the case, and somebody pursues a completely different career because they didn't apply equal rigor [when researching their options], so that they start a different charity that's less effective. Of course, that [results in] real consequences for the beings we want to help.

So why does this happen?

First of all, [it may be due to] a lack of research. If you're working with a small evidence base, there's no research to which you can compare your [initial idea]. Or maybe there isn’t enough data that has been gathered in a similar manner, so you cannot compare it with the same rigor. [An easier problem to solve] is the lack of a system or research process to ensure that, at the end, you compare all of the options. [Without that], then comparison won't happen.

Also, if we don't have a pre-set process — a framework and questions — we might end up with a situation where we're exploring a given area just because there's more information available there. Instead of looking at the information we need, we look at the information we have and base our research on that.

And the last, very human reason is just curiosity. It's very tempting as a researcher to follow a lead that you’ve discovered [and give less attention to comparable ideas]. I fully understand that. I think a lot of researchers decided to become researchers because of this truth-seeking drive. They want to find everything and have knowledge about the entire area they’re exploring.

————

If you're convinced that there are benefits of doing systematic research, there are two simple methods to go about that.

First, use spreadsheets to make good decisions. Do you remember the example of [people’s confidence in] charities going up and down? That could have been prevented had they simply used a spreadsheet [to compare different ideas in one place, rather than changing their views with each new idea they explored]. The model isn't particularly novel, but I think it's quite underused, especially given the body of evidence from decision-making science that suggests it is very effective. The whole process is explained in Peter Hurford's blog post on the topic. I'm just going to summarize the main steps.

First, state your goal. For example, it could be, "What charity do I want to start?" You need to brainstorm many possible interventions and solutions. Next, create criteria for evaluating those solutions — and custom weights for each criterion. Then, come up with research questions that will answer and help you to evaluate each of the ideas in terms of the criterion. At the end, you can look at the ideas’ ratings, sort them, and see which ideas are the three most plausible ones. Of course, this won’t provide an ultimate answer, but at least it will narrow down [your options] from 1,000 things you could do to the top three to explore and test in real life.

We need to not only compare alternatives, but also apply equal rigor. So how do we do that?

Pre-set a research process. Come up with research questions [ahead of time] that will help you determine how well each solution fits each criterion. And I’ll add a few things:

- Formulate a coherent epidemiology and transparent strategies for how to combine different evidence. For example, how much weight do you put on a cost-effectiveness analysis compared to experts’ opinions or evidence from a study? If we're looking at the study, what's more important — results from an RCT or an observational study? How much more important?

- Have clearly defined criteria to evaluate options. How much weight does each criterion carry? Create pre-set questions that will help you rate each idea on each criterion. So for example, you might have a criterion [related to] scale. What exactly do you mean by “scale” — the scale of the problem, or the scale of the effect you can have with your actions? Having very specific questions defining your criteria will help you make [your analysis] cross-comparable.

- Decide how many hours you're going to put into researching each of the questions and apply that time equally. This will increase the odds of your research being consistent and cross-applicable.

Lesson No. 3: Design research to affect decision-making

We know that our goal is to have the highest impact possible. That's why we need to think about designing our research process in a way that affects decision-making. I know that the path is not obvious, especially for research organizations, where the metrics of success are not that tangible and we do not always have a clear and testable hypothesis about how impact will occur as a result of our actions.

That may lead to a few problems. First of all, our research might be ineffective, or less effective, if we don't have a clearly defined goal and [plan for] how our actions will lead to [that goal]. It's very hard to design a monitoring and evaluation system to ensure that we are on the right track. As a result, we might end up not knowing that we don't have any impact.

Second, it's very hard to find assumptions and mitigate risk if we don't have a clear path to impact. There's a whole range of hidden assumptions we're making [to create the] underlying design of our research process, and if they are left unchallenged, it can lead to one of the steps failing and making your project less effective.

Next, [consider your] research team. They might not have a shared understanding of the project, and therefore it could be harder for them to stay on track. Simply put, they might feel less motivated because they don't see how their specific actions — for example, the research paper they're writing — is connected to the long-term impact.

Finally, it's very hard to communicate complex research in your initiative if you don't have a clear path to impact. It’s harder to quickly convey the aims of your work to your stakeholders, decision-makers, funders, or organizations you want to collaborate with.

It's also very hard to reach agreement among your stakeholders. Very likely, the main way your research could have an impact will be informing other decision-makers in the space: funders, organizations [that directly provide interventions], and other researchers. But if we don’t directly involve decision-makers in creating our agenda, we won't ensure that our research will be used.

Do you remember those studies from the beginning [of my talk] — the ones about the Eiffel Tower, crocodiles, and sheep? Well, unfortunately, [those kinds of studies occur] in public health, economics, and global development — the domains I care about. There's this notion that [conducting research in the] social sciences, as with any other science, [will result in] something that eventually changes the world. That's why the current focus is on creating good study design.

Instead, we should be focusing on creating good research questions. [Transcriber’s note: Even a well-designed study won’t have much impact if it doesn’t seek to answer an important question.] We have to have a more planned, applied approach. If a researcher and funder are looking at those studies, they might see that an intervention may ultimately lead to impact. They also might realize there are some missing pieces that'll stop you from having impact.

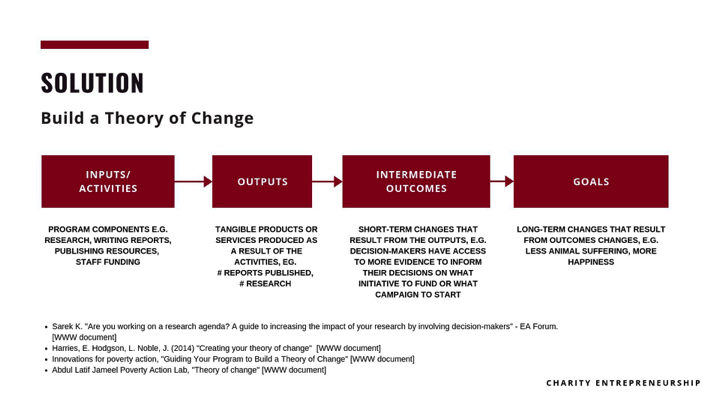

So how do we prevent that? You can build a theory of change. It's a methodology that is very commonly used in global development and [direct-service] organizations, but I think we can cross-apply it to research organizations. Initially, it’s a comprehensive description and illustration of how and why desired change is suspected to happen as a result of your action.

I won't go into details on how to build a theory of change. I'm just going to present the core [elements].

First, you look at the inputs and your activities. [Those represent] the programmatic competence of your organization. They might include presenting at conferences, doing research, and writing. Then, you look at the outputs. Those could include writing three research reports, or answering 10 research questions. Then, you look at the intimated outcomes of your actions. Maybe a funder decides to fund different projects [than the ones they selected] before your research was published. And lastly, you look at the goal that I think we all share, which is to reduce suffering and increase happiness.

So that's the core of your theory of change. And I'm going to present one example of that, which I think is one of the best illustrations of applying a theory of change.

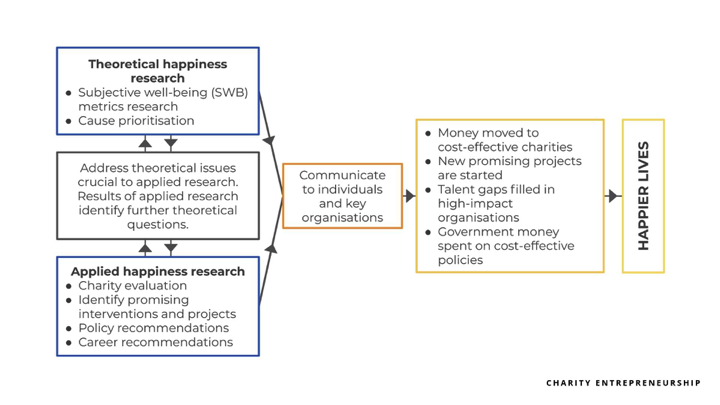

The Happier Lives Institute, an organization started by Michael Plant and Clare Donaldson, built a beautiful theory of change.

As you can see, they considered multiple paths for having an impact, but ultimately it can be summarized in this simple theory of change. They conduct theoretical happiness research. For example, they look at subjective well-being as a metric. Also, they do applied happiness research, evaluating charities and identifying promising interventions and projects. Then, they communicate to key organizations and individuals, hoping to [bring about] very tangible results. Ultimately, their goal is happier lives.

You not only need to build a theory of change to know your impact. You also need to involve stakeholders to create an effective research agenda. You might recognize [the above] spreadsheet. But this time, instead of listing interventions, we have specific research questions we're thinking about exploring. Instead of criteria, there are different decision-makers. It might be a funder that other organizations want to collaborate with.

In this situation, you can ask each of them to rate each of their research questions on a scale from zero to 10, asking how useful it would be for you to have an answer. When everybody fills up [the spreadsheet with their] answers, you can simply sort it and see which research questions will affect their actions and decisions the most.

Summary

I'll summarize the main principles [of my talk]:

- Each piece of research needs to have a conclusion. If not for that principle, I might have researched the exact level of cortisol in fish and how it affects water quality. But I wouldn't be able to introduce you to the Fish Welfare Initiative, an organization working on improving the welfare of fish. They got started this year as a resident of [Charity Entrepreneurship’s] research incubation program.

- We also need to have a sense of how the intervention we are researching compares to other options. If not for this principle, I would [know the precise] effect of iodine supplementation, but I wouldn't have compared it to folic acid and iron fortification. I wouldn't be able to announce that Fortify Health, pursuing the latter, has recently received its second GiveWell Incubation Grant of $1 million and is on its way to becoming a GiveWell-recommended charity.

- The last key element of impactful research is [the relevance of your research to] decision-making in your field and the decision-makers whom you might affect. To ensure that your research will be utilized, root it in a theory of change and involve the decision-makers to create an impactful research agenda. Without this approach, I’d know exactly how many cigarettes are sold in Greece, but I wouldn't be able to introduce two charities working on tobacco taxation.

As effective altruists’ motto goes, we need to not only figure out how we can use our resources to help others the most, but also [how to do it] through the [intervention we’re considering]. So let's close this gap between research and decision-making, and make research matter. Thank you.

Moderator: You mentioned that when research concludes that more research is needed, it's really important for us to do that [follow-up] research. But I think one of the problems is that those [follow-up] research questions are just inherently less interesting to researchers than novel questions. So how do we better incentivize that work?

Karolina: Yeah, that's a very good question. I think it really depends on the community you're in. If you're in a community of effective altruists, we all agree that our main driver might be altruism and the impact we can have through our research. So that’s the biggest incentive.

We just need to remind ourselves and all researchers [in the effective altruism community] that their research is not just an intellectual pursuit, it's also something that can change the lives of other beings. Having this in mind will help you choose the better research question that is not only interesting, but also impactful.

Moderator: Great. Thank you.

Karolina: Thank you.