Articles

Sam Carter: Are cash transfers the best policy option?

Sam Carter: Are cash transfers the best policy option?

Cash transfers are a popular strategy for poverty reduction. But how do their results compare to those of more traditional programs? In this talk, Sam Carter, a senior policy associate at J-PAL, shares evidence from impact evaluations spanning a set of countries that have directly compared cash transfers to other interventions. She also discusses how their impacts differ, as well as the most appropriate contexts in which to implement transfer programs.

We’ve lightly edited Sam’s talk for clarity. You can also watch it on YouTube and discuss it on the EA Forum.

The Talk

Today I'm going to talk to you about evidence from RCTs [randomized controlled trials] that have directly compared cash transfers to other types of policy interventions.

But first, I want to briefly introduce J-PAL and what we do.

J-PAL is a research center based at MIT. We were founded in 2003 by [Abhijit Banerjee, Esther Duflo, and Sendhil Mullainathan]. You may have heard of [ Abhijit Banerjee and Esther Duflo] given the news about the 2019 Nobel Prize in Economics [they were the recipients, along with Michael Kremer].

We work with about 200 researchers based at universities around the world. They are connected by their use of randomized evaluations to measure the impacts of social programs and policies.

Collectively, the members of this network have conducted almost 1,000 randomized evaluations in 83 countries around the world, spanning traditional topics associated with global development — including health and education — but also more innovative areas like firms and gender.

At J-PAL, we do more than just contribute to the generation of this evidence. We also try to connect the dots from research into action. That involves:

- Generating new studies in areas that policymakers question us about, and for which we don't have ready answers.

- Conducting policy outreach to help summarize and synthesize the evidence from RCTs so that they can be used by the people making decisions about these programs every day.

- Building capacity to help partners generate their own randomized evaluations and use the evidence that already exists to inform their program design.

- Building operations and a system that allows all of this work to happen on its own more regularly.

We work from our global headquarters at MIT and with a network of six regional offices based at universities around the world. We bring global knowledge to local contexts through staff who live in each country and work directly with policymakers on the priorities that they face every day.

We also work very closely with Innovations for Poverty Action (IPA), which is a sister organization both in practice and literally (because it's led by the sister of Esther Duflo, one of our founders and directors). We share a network of regional offices at J-PAL and country offices at IPA, which do the same work to generate and support the use of randomized evaluations.

We're talking about cash transfers because there's widespread consensus that they are a promising strategy for improving lives. There are randomized evaluations and literature reviews showing that cash transfers are impactful in improving consumption, business investment, school attendance, and health-promoting behaviors and services. There's also some evidence that they can reduce violence against women. And there’s little evidence that cash transfers discourage recipients from working, or that they increase spending on temptation goods like alcohol and tobacco, or foods like donuts and candy.

There also has been quite a lot of discussion about cash transfers due to interest in universal basic income, and the question of whether it’s a promising solution to poverty-related challenges or those related to increasing automation and the future of work.

Plus, there’s just a strong evidence base on cash transfers that many of us are very excited to build on.

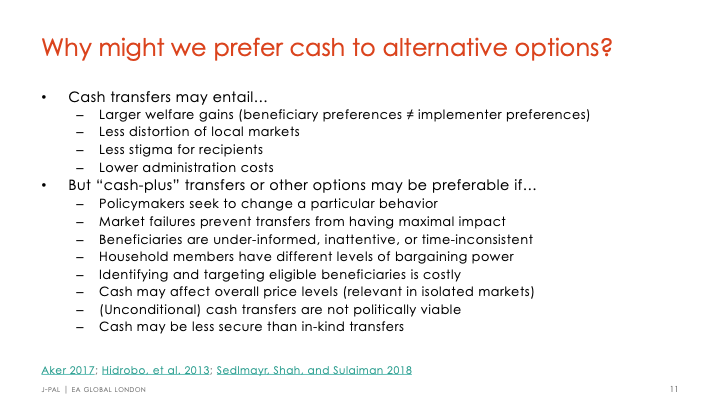

As responsible members of the effective altruism movement, we need to be asking questions about whether cash transfers are actually better than the alternatives that are available to us. Why might we prefer cash to the alternatives?

- Cash transfers may entail larger welfare gains on average if beneficiary preferences don't match implementer preferences [that is, if what beneficiaries want to spend money on differs from what implementers would purchase for them]. From the work that IDinsight and GiveWell do, we’ve seen that this is in fact the case — at least as far as we can tell today. Therefore, we must make sure that we match the preferences of the people we're trying to help as much as possible.

- There's a possibility that cash transfers lead to less distortion of local markets if we refrain from [providing people with] new goods that could be produced by those markets themselves, and instead allow people to engage with the markets more effectively.

- Cash might involve less stigma for recipients if they are able to conceal the cash that they're receiving [whereas other goods might be harder to hide], or if it's not associated with being part of a development program [whereas other goods might have more obviously been provided by a program].

- Cash is quite efficient in most places. It's easy to administer, especially when solutions like mobile money and other direct-deposit options exist.

There are, of course, reasons that we might not prefer cash transfers to the alternatives:

- In-kind or cash-plus interventions might be preferable if policymakers want to change a particular behavior or increase consumption of a particular good. We must ask: Who gets to make those choices? But if the goal is to increase education or consumption of one particular thing, it might make sense to do interventions that are more targeted to those specific outcomes.

- There are market failures that prevent transfers from having the maximal impact. If it's really costly or even impossible for recipients to use cash to purchase something like a business training program, it might make more sense to be delivering that program directly, rather than giving cash and expecting recipients to invest in it when they can't.

- There are different levels of bargaining power within a household. For example, if we're trying to improve outcomes for women or children, it might make more sense to just give them the goods. That way, they don't need to have decision-making discussions within their households about how to spend the cash.

- Self-targeting is a lot more likely to be effective if we don't have the resources or the ability to identify eligible recipients of our program. In those cases, it might make more sense to ask recipients to sign up for or collect in-kind or other types of transfers.

- There's some evidence that cash could affect overall price levels. This is particularly relevant in markets that are quite isolated from the other markets around them. If cash is just not a politically viable option, we still want, of course, to be helpful.

- Cash may be less secure than in-kind transfers. It might be easier to steal; it's quite portable.

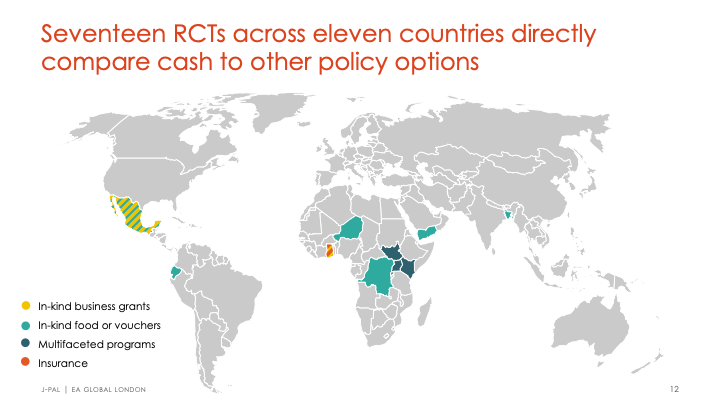

When we have these questions, we want to turn to the evidence. Today I'm going to share results from 17 RCTs across 11 countries that directly compare cash to other policy options. We'll discuss in-kind business grants versus unconditional cash grants, in-kind food or food vouchers, multifaceted programs that are often called “the graduation approach” or “graduation programs,” and one RCT that looked at insurance versus cash transfers for farmers.

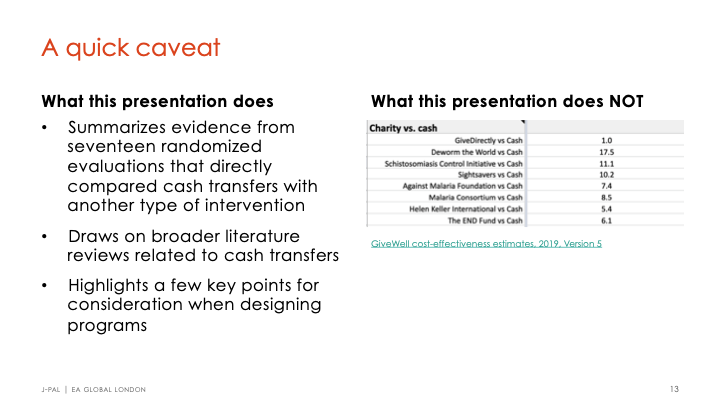

A quick caveat before we dive in: This presentation summarizes evidence from these RCTs and draws on broader literature reviews, as well as broader evidence about cash transfers. Our goal is to highlight a few key points and give people who are interested in designing, implementing, and funding programs to reduce poverty a sense of what the evidence currently says. We are not trying to make any claims about what is definitely the most cost-effective or effective intervention.

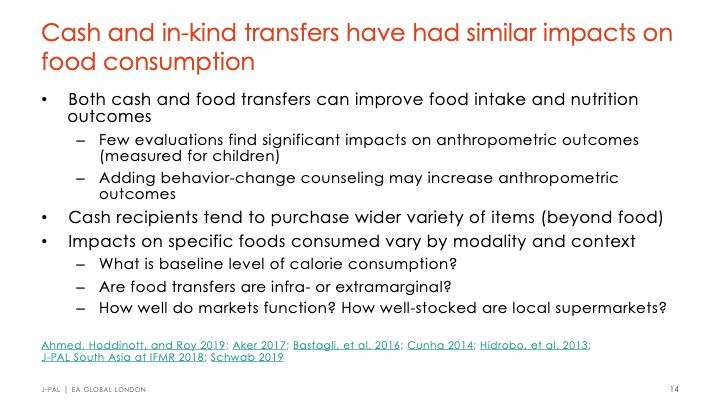

Let’s look at three broad types of impacts that we might care about. The first is on nutrition and food consumption. Both cash and food transfers have been found in RCTs to improve food intake and nutrition outcomes like dietary diversity and number of calories consumed.

Few evaluations find significant impacts on anthropometric outcomes like height or weight for age. Hypotheses explaining why include low statistical power to measure these outcomes, or alternative environmental factors that prevent improved nutritional intake from having impacts on health. For example, poor water and sanitation in a particular area might prevent children or others from absorbing nutrients from more nutritious food.

There's also some evidence that adding behavior change counseling improves these outcomes. That could suggest that there's something else going on within a household preventing anthropometric outcomes from being evident from giving cash transfers alone. And we see that cash recipients, as we might expect, tend to purchase a wider variety of items beyond food.

We also see that the impacts on the specific foods consumed vary both by transfer modality and by context. There is a big question around the baseline level of calorie consumption. In many cases, if households have a very low initial level of calorie consumption, we see some evidence that they prefer to increase the quantity of calories they consume before increasing the quality of calories. That would have implications for the differential impacts of cash versus in-kind food.

In addition, we need to think about whether food transfers are inframarginal, meaning that they provide food that households would purchase anyway, or extramarginal, meaning that they provide some amount of food on top of what the households would purchase if they had the same amount of cash. That affects the differential impacts. And then we have to consider just how well markets are functioning — how easy it is to purchase the food that would be given in a food basket in a particular context. If it's difficult to purchase something like improved grains in a particular area, then providing those grains will increase households’ consumption more effectively than giving cash.

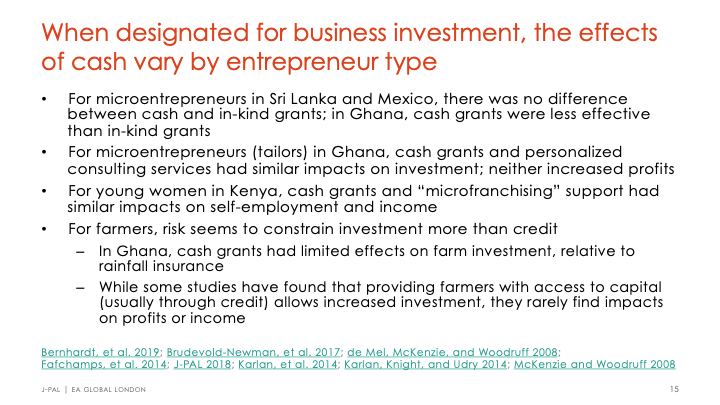

What about business investment? The effects of cash versus in-kind food or training programs vary, depending on the type of entrepreneur being targeted. For programs that gave micro-entrepreneurs either in-kind assets for their business or a cash grant of the same amount of money, researchers in Sri Lanka and Mexico found positive impacts on profits and no difference between cash and in-kind grants.

In Ghana, on the other hand, researchers found that cash was less effective than in-kind grants. When they looked into why that might be, they found that self-control might be involved. When people received cash, they had a harder time keeping it invested in the business than if they’d received an asset purchased especially for the business.

It’s interesting to think about what that means for programming. For a different study in Ghana that was working with small-scale tailors, researchers tested cash grants versus personalized consulting services. They found that both had similar impacts on investment in the business, but neither was able to increase profits overall. Their hypothesis is that the grants and the consulting allowed the entrepreneurs to test out new business investments or strategies, but that after a little while they just reverted to what they’d been doing before the program was implemented. In Kenya, on the other hand, a program that gave young women either cash grants or support to operate micro-franchises of popular businesses in that region found that each program had similar impacts on how many hours women spent in self-employment and on their incomes, but that both of these effects faded after about two years.

For farmers, risk is a bigger constraint to investment in farms and in improving farm productivity than credit. One study in Ghana found that cash grants had limited effects on farm investment, but that providing rainfall insurance, which allowed farmers to cope with the risk that weather might affect their farm poorly in a particular season, allowed them to increase their investment in their farm.

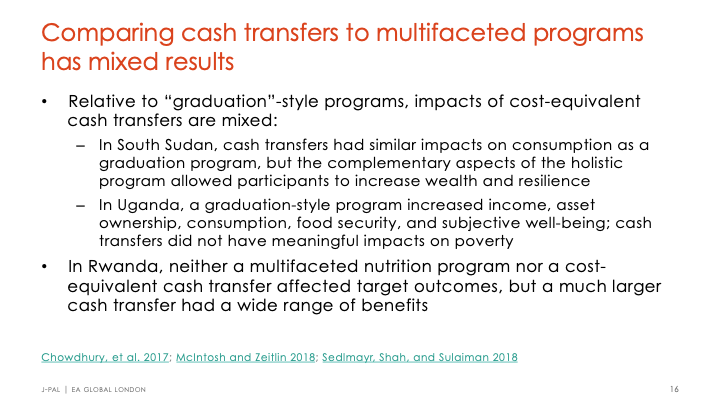

Next, let’s look at a broader set of multifaceted programs with more diffuse goals in mind. Graduation-style programs [programs designed to help people “graduate” out of poverty over time] have multiple components that address overlapping constraints facing very vulnerable households. There are two studies that have directly compared these programs to cost-equivalent cash transfers.

The first, in South Sudan, found that cash transfers had similar impacts on consumption as the holistic program — but that the complementary aspects of the holistic program allowed participants to increase their wealth and resilience to violence, while the cash grants alone did not allow them to do that. This aligns with what we’ve seen in Uganda, where a graduation-style program increased a number of outcomes, including income, asset ownership, food security, and subjective well-being.

Cash transfers, on the other hand, did not have meaningful impacts on any of these outcomes. There's definitely something to be said for the complementary aspects of these types of programs having a positive impact on recipients.

Finally, there was a program in Rwanda that was explicitly designed as a benchmarking program for a traditional development intervention. It was intended to improve nutrition and health outcomes for children under five. The cash transfer was equivalent to the cost of delivering that program, and the program itself had no impacts on children's health. But a much larger cash transfer had a wide range of benefits on the outcomes that the implementers were trying to attain. Therefore, I think we need to be aware that different amounts of cash will have different impacts.

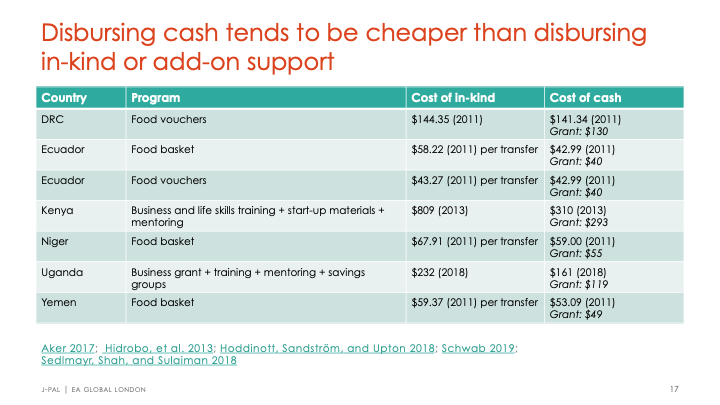

In addition to the impact question, there’s the question of cost. Disbursing cash tends to be cheaper than dispersing in-kind or cash-plus interventions. In the set of six RCTs on the above slide, where they reported cost numbers for both types of interventions, we see unequivocally that delivering cash is cheaper than the cost of delivering the full in-kind program. That’s not surprising.

We also see that beneficiaries may prefer cash over in-kind transfers. In Ecuador, our researchers found that collecting food was costlier to beneficiaries than collecting cash or vouchers for food, and beneficiaries indicated that they preferred cash. Another study in Yemen found that collecting cash was costlier than collecting food. But this was due to the way that the program was implemented, and the food being offered at more convenient distribution points. Something to keep in mind when we're thinking about programs is how they're going to be delivered.

In a program that worked with internally displaced persons in camps in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, researchers found that cash was easier to conceal and more secure than vouchers. This was largely because households were able to spend the cash whenever they wanted to, rather than having to go to voucher fairs that were set up at specific times and in specific locations. (It was easy to identify who received the vouchers, because they attended these fairs.)

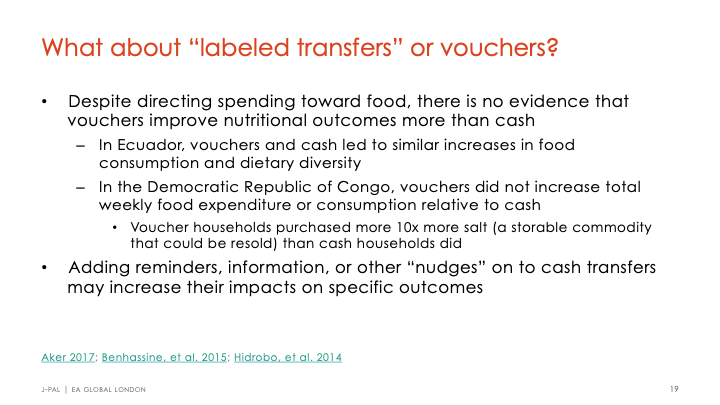

We can think of labeled transfers or vouchers as a middle ground between the flexibility of cash and the direct control of in-kind programs. We see from a few studies that although vouchers funnel spending toward food, there's no evidence that they improve nutritional outcomes more than cash does. And in the Democratic Republic of Congo, researchers found that vouchers allowed households to purchase salt in much larger quantities than households receiving cash.

When recipients were asked about this, they said that they could sell the salt much more easily than the other items that were available at the voucher fair. That suggests they were seeking the same flexibility that the cash would have offered them. Therefore, we can consider adding reminders, information, or other sorts of nudges to cash transfers. Doing so may increase their impacts on specific outcomes without taking away the flexibility that beneficiaries seem to prefer with cash.

Here are some concluding thoughts and ideas for policy implications stemming from this broad sweep of the literature on cash transfers:

- Clearly, cash transfers remain an attractive policy option. They tend to have positive effects, at least in the short term, and they're relatively easy to implement and lower-cost to implement than some of these other alternatives.

- However, cash transfers are not the most impactful option for every outcome. Thinking about our goals is really important before designing a program.

- Increased evidence can help policymakers weigh the tradeoffs that they face when they're designing and implementing programs. Learning more about beneficiary preferences allows implementers to address the tension between providing beneficiaries with autonomy and having impacts on specific outcomes. Also, it can help us evaluate the tradeoff between the number of people reached by a particular program and the size of the impact per person.

- In the future, we can think about leveraging cash-transfer infrastructure to deliver complementary interventions, especially if we're working with mobile phones or other easy distribution points. We can look into the different components of multifaceted programs and identify which are the most impactful, and how to deliver them more cost-effectively.

Nathan Labenz (Moderator): An initial question concerns the difference between the distribution of outcomes versus the mean. Do you have any information on how those may change? For example, an audience member is wondering about worst-case scenarios. You might worry that for somebody who struggles with addiction, cash could be particularly bad, and you might have some outliers. I'm sure we could come up with a positive scenario for that as well. But do you know how the distributions vary, as opposed to just comparing mean outcomes?

Sam: That's a really good question. Something to keep in mind is that for any sort of “headline” result from an RCT, we are looking at the average in the treatment group relative to the average in the comparison group. Of course there's always the possibility that one person, or some people, were negatively impacted, even if the overall impact was positive. Similarly, there's always potential for just a big distribution of impacts.

The results that I presented all reflect scenarios in which there’s been enough statistical significance and precision to say that these impacts are, at least on average, holding. But I don't have a ready-made answer, especially about each of these programs. I encourage everyone to look at the papers [referenced] in the slides.

Nathan: Another audience question is about the timescale of these studies. Could you give us a bit of information on how long they ran? Also, beyond the length of the actual study itself, what do we know about how persistent the positive effects are? Should we assume that if a program ends, recipients won’t get cash anymore, but if they’ve been “taught to fish,” [metaphorically speaking], they can theoretically fish forever? How might we think about that?

Sam: The number of RCTs that have long-run follow-ups is still pretty small. I can say that there is some evidence from one graduation or holistic program in India and Bangladesh that the impacts continue to persist for at least seven years after the intervention is over. That does seem to be a case in which we are effectively teaching people — in this particular case, women — how to run sustainable micro-enterprises that help them get on a sustainable path out of poverty.

For cash transfers, there are a few studies that have looked at really long-run outcomes. We can see from a study in Kenya with GiveDirectly, and a study that, I believe, took place in Uganda, that impacts do tend to fade over time. That’s not surprising given that, as you said, we're no longer giving cash.

It does seem to be the case that giving cash transfers, even over the course of nine months or a year, doesn't allow people to invest or get over whatever hurdle was preventing them from having higher incomes. There’s still room to study this. And I think there could be ways that we can encourage people to invest or save cash when they receive it. But as it's being given out now, the results are not super exciting for the very long haul.

Nathan: What about the conditional cash-transfer model? Is that a way to get the best of both worlds by both spurring the behavior that you want and just giving cash when it happens?

Sam: Yeah, conditional cash transfers are designed to do exactly that. They encourage investments in human capital, which ideally will help households get out of poverty while still providing consumption support in the immediate term. I'm not as well-versed in that literature. I know it's a lot broader than what I've presented here today, which involved largely unconditional programs. But I do think conditional cash transfers have promising results, at least for getting children into school and getting households to take up healthy behaviors. I haven't seen much evidence in either direction on the longer-term impacts.

Nathan: Okay. Which of the potential downsides of cash transfers, such as unequal bargaining power in households and potential market failures, do you worry may be the most difficult to untangle and measure?

Sam: I think one that I'm excited to see more research on is on the question of spillovers to households that don't receive cash or communities that aren't receiving cash transfers overall. There's some evidence pointing to psychological impacts on households that are near households that receive cash, but that don't receive it themselves.

The intra-household bargaining power question is interesting. In one of the studies that I mentioned, when in-kind or cash grants were given to micro-enterprise owners, researchers found that women didn't see positive impacts on income or profits, on average. But that was only the case for women who had another enterprise that existed in their households. So women were most likely investing the cash in their husbands’ or other household members’ enterprises instead of their own. How we measure these things is really important; whether it's at the household level or at the enterprise level could give us different answers.

Nathan: How do you — as someone who is coming from a totally different part of the world and running experiments in faraway places — approach the ethical questions bound up in that? How do you make sure that people are given agency and treated with the individual respect that they deserve?

Sam: Yeah, that’s hugely important. We're lucky to work with researchers who think about that quite a lot when they're working with local partners on designing these interventions or measuring interventions that local partners have designed themselves. It’s rarely the case that the researchers are sitting in their ivory towers designing things and then rolling them out on the ground.

I think we always need to stay humble and keep asking questions. As Dan Brown mentioned in his EA Global talk, we must consider all of the ways that things can go wrong and do our best to mitigate against those possibilities. And we must not only think about them ourselves, but also ask people who are in the situations we're trying to address for their opinions.

Nathan: One audience member has a question about the seeming absence of studies from the Middle East over the last few years. This person has worked in Syria and felt like there were some good lessons learned there. Where does the Middle East fall into all of this?

Sam: I've seen a few studies coming from that region, but they are more recent. I think it probably has to do with research infrastructure and the ease of coming in and delivering programs. Also, I think a lot of the ethical questions about delivering programs in a randomized fashion might be more applicable in a place like the Middle East. I think being responsible about measuring the impact of programs, rather than just delivering them to the people who need them the most, is probably at play there.

Nathan: Awesome. How about another round of applause for J-PAL's Sam Carter?